Return to menu

Topics

Ad hominemAdvance fee scam

All-or-nothing fallacy

Anecdotal experiences

Anger argument

Appeal to authority

Axioms argument

Buffet analogy

Choice argument

Cognitive dissonance

Communists argument

Complexity argument

Confirmation bias

Consequences, appeal to

Contingency argument

Cosmological arguments

Degrees, argument from

Devil argument

Difficulties of the theory

Dogmatism

Dualism argument

Dumpster argument

Dunning-Kruger effect

Emotions, appeal to

Entropy argument

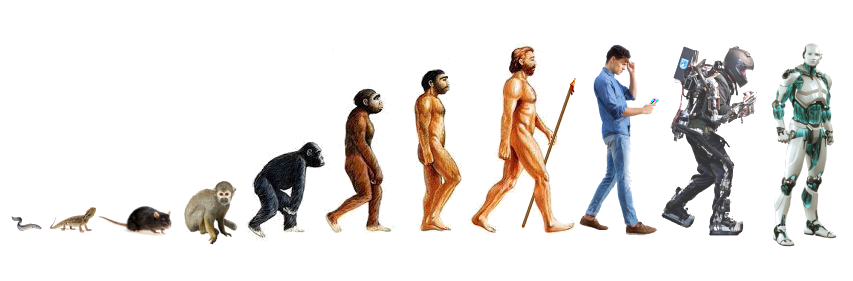

Evolution is compatible

Evolution is not science

Existence demands explanation

Explaining away

Explosion analogy

Faith argument

Faith in science

Faith healings

False dichotomy

Fine-tuning argument

Founding fathers arguments

Free will argument

Fruits

Gaps in the fossil record

Gish gallop

God-of-the-gaps argument

Good effects of religion

Ignorance, argument from

Improbability argument

Incredulity, argument from

Irreducible complexity

Joystick hypothesis

Judgment argument

Kalam cosmological argument

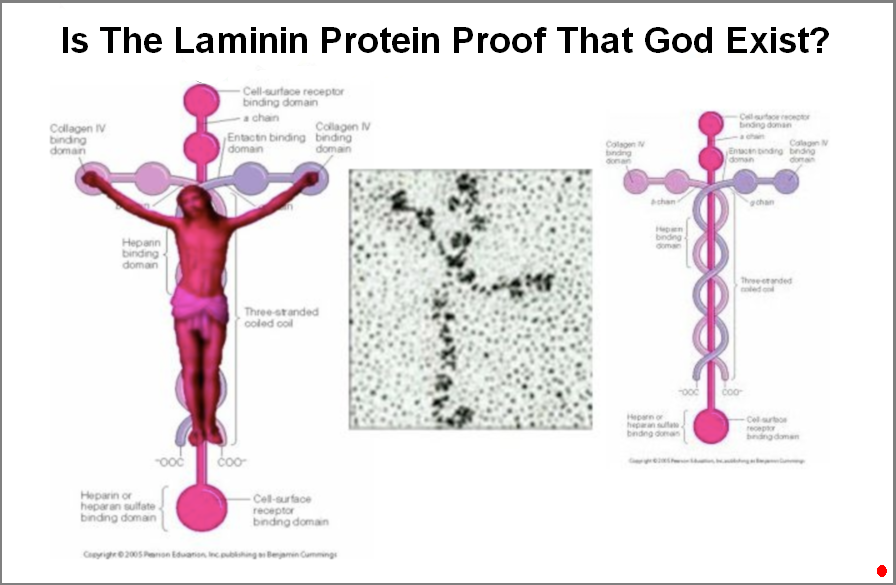

Laminin argument

Laundry list of arguments

Life

Literal places argument

Martyrs argument

Micro-evolution claim

Mind-body problem

Miracles

Morality argument

Mysterious ways justification

Nature argument

Near-death experiences

Neuro-plasticity

New God Argument

Non-overlapping magisteria

Omphalism

Ontological argument

Pants-on-fire argument

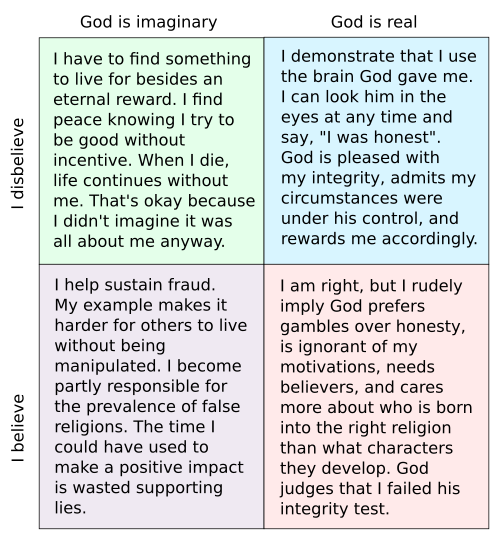

Pascal's wager

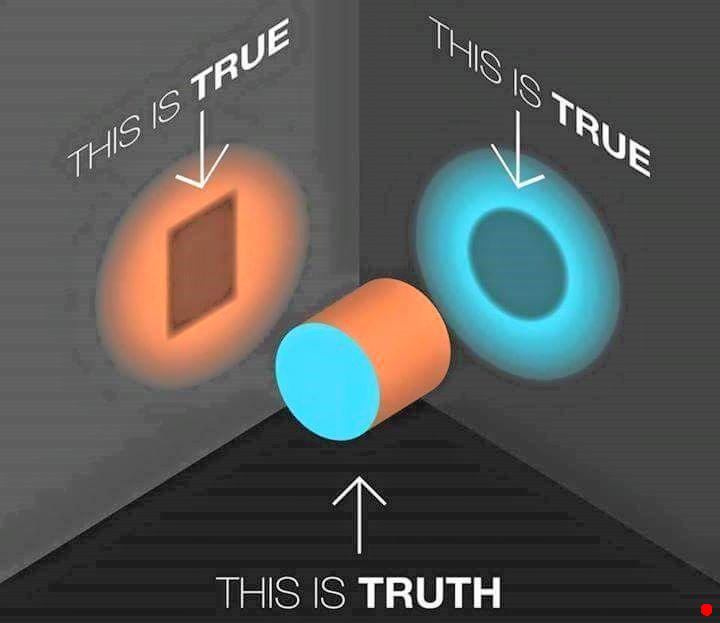

Perspective argument

Placebo effect

Postmortem compensation

Pragmatic argument

Pragmatic Theory of Truth

Pride argument

Prophesies argument

Purpose of life

Reason, argument from

Religious experience

Religious method

Religious scientists argument

Science changes fallacy

Shifting the burden of proof

Simulation argument

Spirit

Supernatural immunity

Teleological argument

Test of faith

Theory/proof fallacy

Timeline of history

Transcendental argument

Trilemma

Uncertainty argument

Vain, taking name of God in

Volunteer clergy argument

Watchmaker analogy

Witness-based arguments

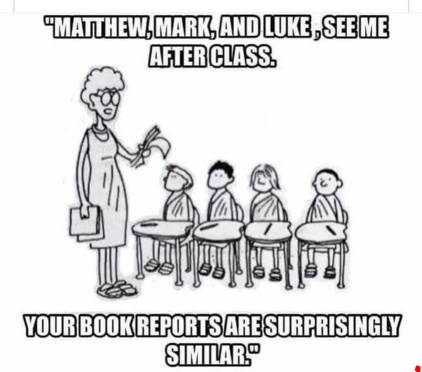

Arguments for God

When I started losing my faith in God, I searched for apologetic arguments that suggested it was rational to believe in him. This is a list of the arguments I found, and some reasons why I cannot honestly accept them.

You may use, derive from, and distribute this document for any purpose. (Note that I put a red dot in the bottom-right corner of graphics I do not own.)

Ad hominem

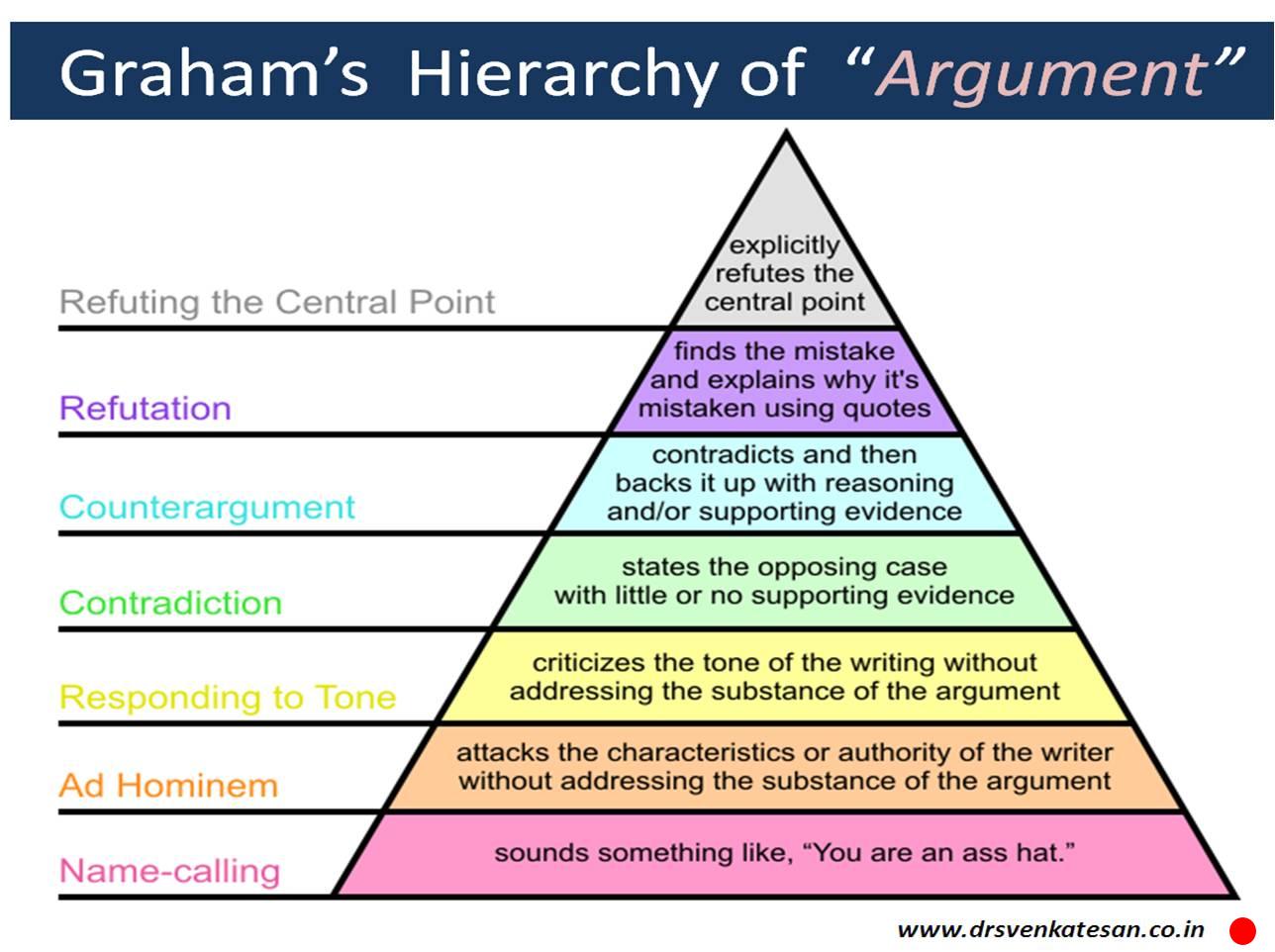

Ad hominem involves attacking the character of one's opponent instead of confronting the reasoning that has been presented. It is a logical fallacy, and it does more to weaken one's position than to strengthen it.

In debate, it is common for people to erroneously suppose that the objective is to prevail over one's opponent at any cost. Thus, when they run out of high-level arguments, it is common to resort to lower levels of childish stubbornness. A much better strategy is to refuse to be baited into debating at a lower level, and if one's reasons are defeated then simply concede. Why? The proper objective in debate is to find truth, and only the person who concedes actually learns from the experience. In the long run, those who are willing to yield when they are wrong will learn how to be right more often, and will no longer need to concede as often. The most useless debates involve two dogmatic people both metaphorically plugging their ears while flinging spurns back and forth. (See dogmatism.)

Despite common assumptions, almost no one's opponent is ever converted mid-debate. But that does not mean debate is pointless. The silent audience that observes the debate is usually both more open-minded and more numerous than one's direct opponent. The silent audience will be keenly aware of the level at which the debate is proceeding, and will be much more impressed with those who are really seeking for truth than with those who are stubbornly trying to prevail. When one of the debaters sincerely acknowledges a good point that his or her opponent has made, the audience is often swayed to begin listen more favorably to the position of the person who is willing to bend.

Advance fee scam

An advance fee scam charges a small fee now in exchange for the promise of a large reward later. A classic example of advance fee scams are the notorious Nigerian Prince scam e-mails. Christianity also has some remarkable similarities with advance fee scams:

- The promised reward is too good to be true.

- The details of the process are vague or incomprehensible.

- The reward is not expected to be delivered until it will be too late to implicate the scammer.

- The advance "fee" seems very nominal by comparison, making the deal extraordinarily appealing by contrast.

- The scammer uses a third party to deliver the promised reward, who is not easily reachable.

All-or-nothing fallacy

The all-or-nothing fallacy attempts to tell people they must accept everything a religion teaches or reject it all. It usually sounds something like this: "The Gospel is not a buffet. One does not just pick the doctrines he finds appealing and leave the rest."

An all-or-nothing attitude attempts to create a dilemma for atheists because there are some very good teachings found in Christianity. However, the scheme backfires when someone decides that they cannot accept the superstitious components of Christianity, and then feel pressured to distance themselves from every aspect of it. One possible resolution is to make sure that this is one of the teachings that is rejected, so that others may be evaluated based on their respective merit.

Another form of the all-or-nothing fallacy suggests that one should commit entirely to an extreme position before fully investigating it. This form of the fallacy is represented in the statement, "Those that are not with us are against us!"

A good way to model beliefs is to use a probability distribution over all plausible hypotheses. In other words, on may continue to consider all hypotheses that may yet turn out to be correct, but only give each one consideration proportional to its plausibility. For example, Bob might recognize that arbitrarily placing 100% of his confidence on just one hypothesis would make him dogmatic, and would prevent him from learning more truth. So instead, he might believe with 20% confidence that humans evolved from primates, and 80% confidence that God manually engineered human DNA, then adjust those probabilities as he becomes familiar with more evidence. By giving consideration to multiple conflicting hypotheses, Bob will be able to maintain an open mind, but will still able to converge to certainty as he compares the available evidence for both hypotheses.

Anecdotal experiences

An anecdotal experience is an attempt to establish the truth of some principle based on a personal story that cannot be reproduced or validated. Some common examples include miracle stories and near-death experiences. Because the conditions of an anecdotal experience cannot be deliberately reproduced, they are difficult to disprove. Consequently, they are often used in attempt to shift the burden of proof onto the skeptic. Unfortunately, people are usually subconsciously aware of the fact that their anecdotal experiences cannot be scrutinized, so there is a strong tendency to strengthen them by exaggerating aspects of certainty. This results in the telephone effect, and makes anecdotal experiences extremely unreliable. (See also Witness arguments.)

Anger argument

The anger argument suggests that atheists imply the existence of God with their own opposition to him. It usually sounds something like this:

- Atheists are not angry at unicorns because unicorns are not real.

- Atheists are not angry at leprechauns because leprechauns are not real.

- Atheists are angry at God because God is real.

The primary assumption of the anger argument is that atheists are angry at God. This is usually caused by a misunderstanding that may have originated from a miscommunication, such as follows:

In cases where anger actually is present in atheists, it is usually directed at the people who have misinterpreted their position, or the organizations that they feel have been misleading. When they refer to God, they are trying to speak hypothetically, as if he existed. It is a sincere attempt to communicate with someone they understand believes in God. Suggesting atheists are angry at God shows a lack of understanding about what they believe. This makes the atheists feel misrepresented, and reinforces the misunderstanding.

A second major fallacy of the anger argument is that the conclusion does not follow from the premise. One may become angry for rational or irrational reasons, so concluding God exists because atheists are angry is a pretty flimsy basis for his existence.

Appeal to authority

An appeal to authority attempts to establish the truth of something based on a supposedly unquestionable source. However, science does not recognize any individual, panel, group, or organization as having any authority. Galileo Galilei described it well:

As an example, suppose Charlie wants to convince Alice that God is immune to the investigations of science. He might start by noting that science only investigates matters that can be directly measured, and supernatural things cannot be measured. Then, to add credibility to his position, he might quote a 1999 statement by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, as well as a few other organizations that have made similar observations, and tell Alice that if she does not accept his position then she is not truly aligned with science! Remaining cool-headed, Alice might simply ignore his no-true-Scotsman fallacy and respond with her reasons: She might describe the statistical principle of explaining away, and point out that science does not need to directly investigate any supernatural phenomenon in order to find a more plausible explanation. Since Alice's reasons are sound, no amount of authority can dismiss her position, and because she refuses to be baited into arguing at a lower level, Charlie will be forced to confront her reasoning--the highest level of argument.

Axioms argument

Every explanation ultimately depends on a set of axioms--simple truths that are taken for granted. Sometimes, theists argue that scientific explanations are no better than religious explanations because they all can be reduced to some set of axioms. The fallacy is that scientific axioms are simple and observable, whereas religious axioms are supernatural, immeasurable, and unfathomable. It is one thing to just accept that electrons exist and repel each other as verified by numerous experiments, and quite another to just accept that an omnipotent, omniscient, omnibenevolent, supernatural being who operates in mysterious ways governs the Universe and a certain religion understands all the details without being able to explain why or provide any mechanism to objectively verify its claims. Ultimately, the simplicity and verifiability of the axioms themselves are what give credibility to an otherwise sound explanation.

Buffet analogy

See All or nothing fallacy.Choice argument

The choice argument attempts to blame atheists for their disbelief. It suggests that belief is a choice, and therefore atheists are responsible (or guilty or cowardly) for choosing not to believe in God.

A major assumption of the choice argument is that belief in God is the correct choice. Obviously, the atheist does not agree with this assumption, but this is often not explicitly acknowledged when confronting it. Those who continue to confront the choice argument without acknowledging the assumption are essentially attempting to defend a position that has already been assumed to be wrong.

The dominant choice involved in forming beliefs is whether to be honest or dishonest. Dishonesty with one's self involves allowing for cognitive dissonance by accepting that two or more contradicting concepts are simultaneously true. Ironically, atheism may be the product of a choice to be honest with one's self, and with respect to evidence. Often, the decision to be internally honest is so obviously the right choice that atheists will contend that there is no choice at all involved in what one believes.

Sometimes, theists suggest that atheists should engage in some form of "fake-it-till-you-make" it, where the atheist should suppress his or her disbelief until it goes away. However, this suggestion weakens the validity of the theist's own beliefs by suggesting that they may be the product of a willful choice, and therefore not likely representative of reality or truth.

Cognitive dissonance

Cognitive dissonance occurs when a person holds two beliefs that contradict each other. For example, it may happen when a person is convinced that life evolved on this planet, but simultaneously believes in a religion that teaches God created all things. Since truth does not contradict itself, cognitive dissonance suggests at least one erroneous belief. Unfortunately, the belief that is in error is not always obvious. Many people make the false assumption that cognitive dissonance is an unbearable condition that inevitably causes people to resolve all of the things they believe. In reality, however, humans often live with varying degrees of cognitive dissonance.

When cognitive dissonance occurs, one option is to become dogmatic by arbitrarily throwing out one set of beliefs in order to place full confidence in the other. However, a more objective approach is to give both hypotheses consideration in proportion to their plausibility. Living with cognitive dissonance is certainly not a desirable end state, but it may be a preferable temporary state over arbitrarily choosing beliefs without supporting evidence.

Communists argument

The communists argument sounds something like this:

- Joseph Stalin and Mao Ze Dong were atheists.

- Joseph Stalin and Mao Ze Dong did some very bad things.

- Therefore atheists do bad things.

- Joseph Stalin and Mao Ze Dong were atheists.

- Joseph Stalin and Mao Ze Dong were communists.

- Therefore atheism makes people politically liberal.

The fallacy of the communists argument is that atheism is just disbelief in God. It does not come with any unifying doctrines, so atheists have a wide diversity of beliefs. The absurdity of the argument becomes more apparent if it is reworded as follows:

- Joseph Stalin and Mao Ze Dong ate bread.

- Joseph Stalin and Mao Ze Dong did some very bad things.

- Therefore bread-eaters do bad things.

Like atheism, eating bread does not unify people under a set of common beliefs, so it is not reasonable to assume that people who eat bread are likely to behave in the same way. By contrast, the behavior of Joseph Stalin and Mao Ze Dong could easily be attributed to their extreme idealistic fundamentalism. In many ways, their extreme idealism is much more comparable to what people find in religion than what they find in merely disbelieving in God.

Complexity argument

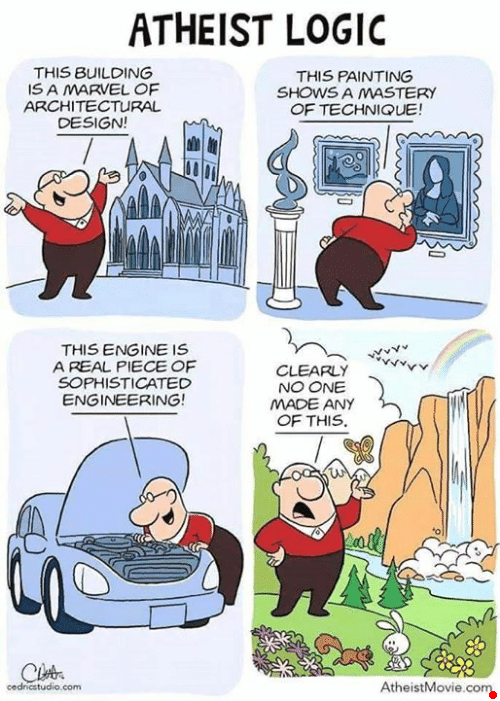

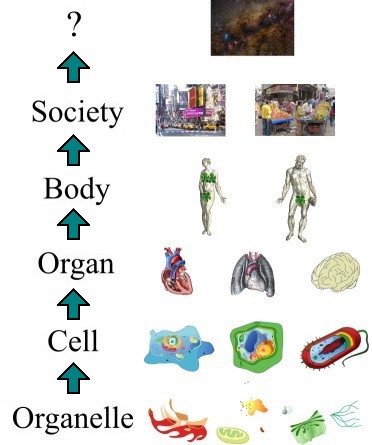

The Complexity argument, or specified complexity argument, claims that life could not have evolved because it is so extremely complex. (It differs from the Improbability argument, which uses complexity to dismiss abiogenesis rather than evolution. Note that both arguments are often made together by citing complexity to dismiss both abiogenesis and evolution.) The Complexity argument is also closely related to the Teleological argument, but the complexity argument focuses on complexity whereas the teleological argument focuses on utility. The following meme attempts to make the complexity argument:

The Complexity argument is almost always the product of lacking understanding about how evolution works. Evolution is one of the most effective methods yet known for refining highly complex things. By contrast, designing complex things is relatively difficult. It follows that an intelligent designer who wanted to create complex creatures would utilize the more effective tool for the job (evolution) rather than do it the hard way (design).

A simple illustration of the effectiveness of evolution can be found in domesticated animals. Why do sheep produce more wool than they need? Because human farmers bred them to produce wool over thousands of years. Did these farmers decode the sheep genome? Did they program the sheep to be fluffy? Certainly not! They just put the fluffiest sheep together and let nature run its course. Why do cows produce more milk than they need? Why are pigs so meaty? All of these are the products of natural processes guided by human intelligence. But none of them are the products of low-level engineering. Animals are far too complex for low-level engineering, but natural processes are highly effective at refining complex things with just a little guidance. Hence, a lot of complexity really implies evolution, rather than intelligent design. Whereas intelligent design would require an extremely intelligent designer capable of manipulating profound complexity, evolution requires only the relatively small step of finding a natural substitute for the task of selective breeding, something uneducated farmers have already achieved. And natural selection fills that small gap quite easily.

Human engineers often utilize genetic algorithms (numerical optimization methods that work by simulating evolution) for refining designs in problem spaces that are too complex for the designer to fully comprehend. Hence, significant complexity does not necessarily suggest that anyone ever comprehended the matter, and probably even suggests that it was not (at least directly) designed at all.

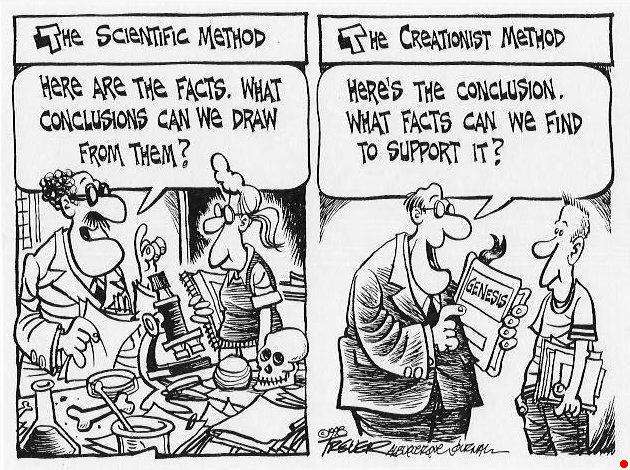

Confirmation bias

People are more likely to search for evidence that supports what they already believe. People are more likely to find, remember, and cite evidence that supports what they already believe (obviously). Thus, people are more likely than not to think that evidence is on their side. This is called confirmation bias.

Confirmation bias can become a fallacy when a person filters a large body of evidence and concludes that there is an overwhelming amount of evidence to support his or her position (often without even realizing that there is also an overwhelming amount of evidence refuting it, or supporting conflicting ideas.) This often manifests itself in the question, "how can you reject this idea when there are so many witnesses confirming its validity?" The same reasoning could be applied to many other ideas. Many witnesses can be found supporting all sorts of conflicting ideas. Thus, any attempt to sample the pool of witnesses must be very careful not to inject bias of any sort into the sample.

Consequences, appeal to

An appeal to consequences is a fallacy that takes this form:

- If P then Q.

- Q would be good.

- Therefore, P must be true.

It is an attempt to derive what "is" from what "ought" to be. Theists often appeal to consequences when they argue that belief in God leads to properity or morality or happiness. Moreover, they imply that God enforces this same fallacy when they imply that belief or unbelief has consequences in the afterlife. None of these appeals to consequences really tell us anything about whether there is a rational basis to suppose God really exists.

Contingency argument

The contingency argument is as folows:

- Every being is either contingent (meaning it was caused by another being) or necessary (meaning it always existed).

- Not every being can be contingent.

- So a necessary being must exist, and we call him "God".

This argument attempts to sneak in the detail about the necessary cause being a "being". Naturalists believe life is ultimately the product of a natural process that began without a conscious being. If one is willing to broaden the definition of God to include whatever actually occurred, then we don't know really know anything about how it occurred--we just have a uselessly broad term. If we accept that term, the person making the argument will probably start trying to attach more specific details to this term. Otherwise, what was the point of calling it God?

Cosmological arguments

Cosmological arguments attempt to prove the existence of God based on the existence of the cosmos. The most popular version is probably the Kalam cosmological argument. Cosmological arguments all take approximately this form.

- Stuff exists.

- Something must have created it or caused that stuff to exist.

- Let's call the creator "God".

Cosmological arguments almost always to exploit ill-defined concepts, such as "exist", "create", and "cause". At first, most people feel these concepts are straight-forward terms they understand well, but they often fail to notice when the argument switches definitions.

For example, what does it mean to "exist"? Things that have physical existence, such as rocks or people, exist because they occupy a place in space and time. By contrast, things only have conceptual existence, such as music or love, exist only because some intelligent being organized them or defined their conceptual boundaries and and gave them names. These two different forms of "existence" are not even the same idea! Indeed, matter exists, but that doesn't mean it was created or organized by an intelligent being like music. Could matter have had physical existence before any intelligent being recognized, giving it conceptual existence? We don't know.

Does the term "created" mean something was organized from existing materials, does it mean something was recognized conceptually, defined, and named, or does it mean caused to occupy a place in space and time ex nihilo? The first premise of cosmological arguments usually invoke physical existence, but the second premise usually reverts to some form of creation that is more applicable to conceptual existence. Just because music had to be organized into conceptual existence does not imply matter needed to be created into physical existence. It's not even clear what that would mean.

And it is easy to assume that a "cause" must necessarily be intelligent. Yet, stellar accretion, solar fusion, plate tectonics, volcanics, evaporation, erosion, evolution, crystallization, and many other natural processes "cause" things to become organized too. Notably, with the evolution of species, we have seen that it is not safe to assume everything that happens is caused by an intelligent designer. It would be foolish to make this same mistake again with the existence of matter.

Sometimes a cosmological argument is made with the simple question, "who detonated the Big Bang?" Yet, as short as this question may be, it makes a great many assumptions, including:

- Matter began to exist at the Big Bang (which is only speculated).

- The Big Bang had an unnatural cause (even though solar fusion and supernovas have natural causes).

- And it weakly implies that cause had some relation to religious mythology.

If we consider only two possibilities, "God always existed, and he created the Universe out of nothing", or "The Universe always existed", then the latter possibility really seems to add fewer superfluous details, especially since we can observe the Universe in existence but cannot easily observe the existence of God. It would be a special pleading fallacy to suppose that the Universe must have a cause, but God does not need one. Ultimately, the cosmological argument reduces to, "why is there something rather than nothing?" The only honest answers to this question will contain some form of, "we don't know", and will not contain, "the true answer is..."

Degrees, argument from

The argument from degrees is an attempt to define God into existence as follows:

- If we were to sort everything in the Universe by greatness, something would be the most great.

- Whatever is the most great, we shall call "God".

- Therefore God must exist.

(Obviously, a similar argument could also be made with respect to knowledge, beauty, or any other attribute by which beings could conceivably be ranked.)

A minor problem with the argument from degrees is that greatness is multi-dimensional. For example, feather dusters are better than apples for brushing dust off of furniture, therefore for the purpose of dusting, feather dusters are better than apples. However, apples are more nutritious than feather dusters, so for the purpose of feeding humans, apples are better than feather dusters. Hence, greatness can only be ranked if a specific way to evaluate it is agreed upon.

Now, suppose some specific mechanism for evaluating greatness is selected and agreed upon. For example, perhaps we will decide to evaluate greatness by administering a particular standardized test. Then, will one individuals score be at least as high as all others? Certainly, but that achievement will not implicitly endow the winner with any particularly godly attributes. For example, suppose some human named Bob turns out to be the winner. What is accomplished by calling Bob "God"? All that does is cheapen the definition of "God" to fit whatever happens to rank the highest on the standardized test. Hence, the argument from degrees just attempts to define God into existence, rather than show that a godly being actually exists.

Devil argument

The devil argument attempts to use the devil to prove the existence of God. It sounds something like this:

- If the devil is real, then God must be real.

- The devil is real.

- Therefore, God must be real.

The "devil" is sometimes replaced with "black magic", "evil spirits", or some other supernatural entity. The devil argument falsely assumes that these other supernatural things are more obviously real than God. However, most atheists to not believe in anything supernatural, including God, the devil, spirits, magic, etc.

Difficulties of the theory

Sometimes theists like to quote from Origin of Species, Chapter VI: Difficulties of the theory, which says:

This is where theists typically stop quoting, but stopping there really changes the meaning of the full quote. The remainder of the quote says:

Dogmatism

Dogmatism occurs when a person pridefully refuses to consider the possibility that he or she may be mistaken in matters of belief. It causes a person to place more confidence in an idea than is justified by any reasonable basis for the confidence. Dogmatism involves an excessive trust in one's self, and consequently a lack of faith in others.

Dogmatism frustrates communication because the dogmatic person will not legitimately consider any suggestions that others make. The dogmatic person assumes a role of superiority in conversations by attempting to influence others without investing any possibility for being influenced him or herself.

Dogmatism also inhibits a person's own ability to progress in the refinement of his or her beliefs. To illustrate this principle, consider a situation in which information about a particular concept is made available incrementally (that is, line upon line, precept upon precept). A non-dogmatic person will make small adjustments to his or her beliefs as the new revelations are received. Over time, this may slowly cause one idea to overtake another idea, changing which idea dominates in the recipient's set of beliefs. By contrast, a dogmatic person has a habit of shifting full confidence toward the idea that currently dominates. Thus, as new information is received, the dogmatic person dismisses its influence, and ultimately never allows any new idea to take root.

It is quite possible to be dogmatic about either belief or non-belief in any subject. Consequently, dogmatism is a problem for both believers and non-believers alike.

One significant cause of dogmatism is having a strong desire to be perceived as being right. By contrast, open minded people would rather find out that they are wrong, so they can become right. Why do people become dogmatic? Do they believe that truth needs them to defend it? Do they fear having to change their beliefs? Do they fear the shame of being discovered in the wrong? Perhaps it is a combination of all of these, but it is clear that there are few valid or good reasons to be dogmatic.

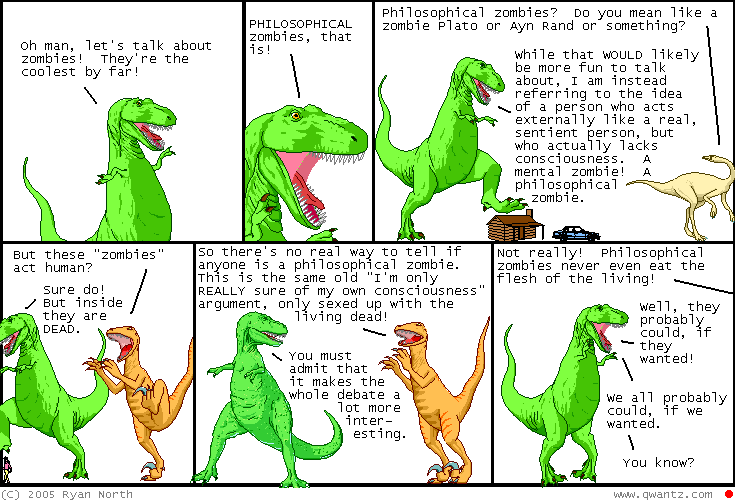

Dualism argument

Dualism is the belief that the processing of information (function) is insufficient to explain consciousness. It stems from Descartes' mind-body problem. If dualism is true, then a simulated brain would never be able to achieve consciousness, no matter how perfect the simulation was, because it would lack the "dual" that makes consciousness work. Although dualism does not directly imply the existence of God, theists often claim that the dual is a spirit that dwells in a supernatural realm, which opens the possibility for resurrection, and an afterlife.

The argument for dualism usually sounds something like this: "I know there is a dual because I can sense that my feelings are so real, and there is no way that function alone could do that." However, the dualism argument essentially reduces to an argument from ignorance. It basically says, "I do not understand how functionalism could produce consciousness, therefore functionalism cannot produce consciousness". But claiming the existence of a dual does nothing to explain consciousness either.

Daniel Dennett is famous, among other things, for identifying that dualism makes the homunculus fallacy. That is, it attempts to explain consciousness by suggesting that there is a conscious component somewhere. The problem is that this creates an infinite regress because then the dual would have to have a dual in order to be conscious.

If a hypothetical machine were functionally equivalent to a conscious being, but lacked the dual, then it follows that the dual could not provide any functional benefit. The machine without the dual would then be indistinguishable from something that was conscious. So the role of the dual could not be to do anything, but merely to exist. Yet, if the brain even so much as had the capability to detect existence, then the dual has has crossed the interface into the functional realm, and could be replaced by something that only simulated the same function.

Dumpster argument

The dumpster argument sounds something like this: "I don't have time to explain or even summarize the reasons for my position to you, but here is a big dumpster (website, book, etc.) containing plenty of details. Please dig through it until you convince yourself that I am right and you are wrong."

The dumpster argument is an attempt to shift the burden of finding a convincing argument onto the skeptic. It is self-evidently an excuse that people make when they lack the ability to defend their positions, but want to claim that they could do so if they were not so busy. If someone actually does invest the time to dig through the metaphorical dumpster, the person making the argument is promoted to a position of power because it is much less work to find new resources than to dig through them.

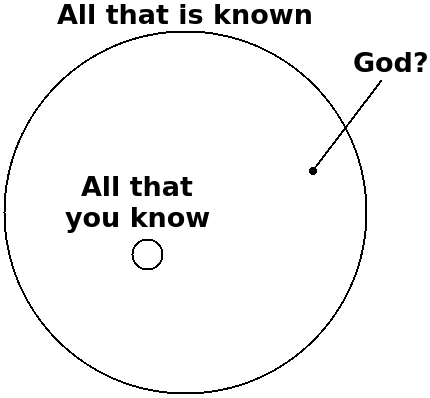

Dunning-Kruger effect

Often, the less people know about a particular subject, the more confident they will be that their opinions on the matter are correct. This is called the Dunning-Kruger effect. Aristotle is reported to have put it this way: "The more you know, the more you know you don't know." The Dunning-Kruger effect creates people who think they are qualified to lead in domains where they have no experience. Some example attitudes that reflect the Dunning-Kruger effect include:

- I don't want to get to know any atheists because they are all hedonists and nihilists.

- I don't want to know how Radiocarbon dating works because it is broken and just gives misleading results.

- Scholars are prideful because they only listen to people with meaningless degrees.

Emotions, appeal to

An appeal to emotions sounds something like, "Jesus loved you so much that he condescended from the glory of his throne in heaven to be born under the lowliest of circumstances. He spent his life serving others, even though he was hated and persecuted for doing good. He suffered more than you can imagine, and ultimately laid down his life for your sins. And all that he requires from you in exchange for his tremendous and loving gift of mercy that will enable you to attain incomprehensible glory for all eternity is that you have faith in him."

Ultimately, it comes across as very petulant for an omniscient being to resort to an emotional appeal without first providing a comprehensible rational basis for what he wants us to believe. It seems more reminiscent of a child trying to invoke emotions in caring parents by harming himself. Indeed, we certainly cannot comprehend what it even means for a deity to suffer. On the one hand, his greatness would exacerbate the magnitude of the contrast, adding insult to his injury. On the other hand, one would expect a god to be more than sufficiently capable of rebounding from finite suffering. Either way, emotions do not point in a clear direction anyway, so it is not at all clear which emotional stories are representative of any sort of actual truth.

Entropy argument

The entropy argument postulates an imaginary law that forbids order from emerging from disorder. If the entropy law were valid, then it would prevent natural evolution from occurring. Because the entropy argument loosely resembles the Second Law of Thermodynamics, some people believe it is an actual physical law. However, no such law has ever actually been established in physics, and numerous natural phenomena demonstrate that it would be false.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics says that the entropy of a closed system cannot decrease. By contrast, the entropy argument claims that the entropy of a system cannot decrease without the application of intelligence. Significantly, the entropy argument claims to apply to all systems, while the Second Law of Thermodynamics applies only to closed systems. Also, the entropy argument implies that it can be circumvented by intelligence, whereas the Second Law of Thermodynamics is believed to always apply.

A closed system is one in which entropy cannot enter or leave. For example, standard air conditioners would not be able to cool a room if the heat-exchanger were kept indoors. However, by putting the heat exchanger outside, air conditioners can cool a room by heating the outside environment. Life is not a closed system. It consumes fuel, emits waste, and interacts with its environment in many ways. Consequently, life is able to decrease in entropy.

A certain thought experiment proposed by James Clerk Maxwell, called Maxwell's Demon, suggested the possibility of circumventing the Second Law of Thermodynamics with the application of intelligence. However, numerous attempts to demonstrate Maxwell's Demon in laboratory experiments have failed to work, and physicists almost universally agree that the Second Law of Thermodynamics cannot be bypassed by intelligence. Confusion about Maxwell's Demon, confusion about the nature of open and closed systems, and an over-zealous desire to disprove evolution are probably all responsible for influencing the formation of the entropy argument.

"Evolution is compatible" assertion

Some non-fundamentalist theists may assert that evolution can be viewed as compatible with the creation story. Specifically, they may say that God could have used evolution in to accomplish the creation. If one is willing to bend some of the finer details of the creation account, or say they are only metaphorical, then this resolution can be made to work.

However, it would be an error to assume that the evolution-creation conflict is the only conflict between religion and science. Evolution is somewhat more difficult to resolve with "the fall" than it is with "the creation". According to the Bible, the fall introduced death into the world, and Jesus was able to bring about resurrection by atoning for the effects of the fall. If, therefore, death occurred prior to Adam (which is strictly necessary for evolution), then another conflict exists with the atonement and resurrection. Another prominent conflict occurs between neuroscience's discovery that the brain is responsible for consciousness and the Biblical claims that consciousness persists after death because of supernatural spirits.

See also Non-overlapping magisteria and explaining away.

"Evolution is not science" assertion

Sometimes theists claim that evolution is not observable, testable, repeatable, or falsifiable, and is therefore not part of science.

However, evolution is observable, testable, repeatable, and falsifiable. Moreover, evolution is the product of many different disciplines of science.

Observable: The theory of evolution was the product of observations made about nature. One can make the very same observations today. For example, squirrels are easy to find, and they appear to be approximately half-way between mice and small monkeys. As our powers of observation have improved, we have observed more evidence that supports evolution inside of individual cells. Here is one of many examples of inter-species evolution being observed in modern times.

Testable: Numerous dating techniques have been developed. They are tested against radioactive decay, which is know to be so reliable that it powers the atomic clocks on GPS satellites. They have been tested against stalagmite accumulation. They have been tested with continental drift with magnetic pole switching. They have been tested against each other, against tree rings and known climate events, cosmic events, etc. There are entire fields of science dedicated to testing dating techniques. Fossils have been dated and those dates confirmed with alternate dating techniques.

Repeatable: Evolution is so reliable that the similar laboratory experiments can reliable anticipate that bacteria will evolve resistance to certain chemicals. Here is a video of such an experiment. Of course, we cannot repeat something that takes millions of years, but we can repeat the same principles in laboratory settings and confirm that they behave as expected. As a simple example, genetic algorithms are an effective optimization technique in the domain of artificial intelligence. They reliably improve with successive generations of simulated evolution.

Falsifiable: The theory of evolution was formed before we had the capability to sequence genomes. If it had been a false theory, that would have been apparent when we started looking at the nucleotide sequences in DNA and found no statistically significant similarity between species that had previously been hypothesized to evolve into each other. To the contrary, the field of phylogenetics was formed, and provides some of the strongest evidence yet available to support the theory of evolution. Moreover, other markers such as mitochondrial DNA have also been found to reliably tell the same story. Indeed, evolution has not been successfully falsified, but it has been subjected to many falsification attempts. In particular, evolution has been a constant target by a large number of theist scientists with significant interest in debunking it. The failure of many attempts to falsify the theory of evolution has been a tremendous boon toward validating it.

Existence demands an explanation

Dissatisfaction with science's inability to explain the origin of space, time, matter, energy, and some of the fundamental laws of nature lead to the following argument:

- The existence of the Universe demands an explanation.

- Science does not know why it exists, but religion teaches that God created it.

- Therefore, we should accept religion.

The fallacy of this reasoning is two-fold: First, it suggests that a made-up-lie is better than no explanation at all, which is self-evidently wrong. Second, the explanation that religion offers is worse than the original problem. If God is even greater and more complex than the Universe he created, then his existence is even more demanding of an explanation. Moreover, his existence is not even as apparent or verifiable as that of the Universe, which further makes the religious explanation incredible. Thus, the least offensive answer currently available to the explanation that existence demands is the dissatisfying but honest one: "We do not yet know".

Explaining away

When a more plausible explanation for something is found, confidence in previous explanations is naturally diminished. This phenomenon is called "explaining away". For example, suppose a violent crime has been committed, and there are only two suspects: Alice and Bob. Based on apparent motives, somewhat more suspicion is initially cast upon Alice than upon Bob. Later, however, DNA evidence strongly suggests that Bob had been at the scene of the crime when it was perpetrated. Since a plausible explanation for the crime has been found, the amount of reasonable suspicion against Alice is greatly diminished, even though no evidence has been found to suggest that Alice was not involved.

Similarly, science does not produce any evidence that directly suggests there is no God. It simply finds natural explanations for various phenomena, and these make supernatural explanations for the same phenomena look silly by comparison. The primary defenses against explaining away are to remain willfully ignorant of scientific explanations, or to misrepresent them in order to try to make them seem as implausible as the supernatural ones. Here are some examples of supernatural phenomena that science has explained away:

| Former supernatural explanation | Branch of science | Natural explanation |

| Clouds are there to hide the dwelling place of God. | Meteorology | Clouds are just water vapor caused by weather patterns. |

| Rainbows are a sign of God's promise never to again flood the Earth. | Physics | Rainbows are caused by the diffraction of light by water particles. |

| Diseases are caused by evil spirits, and are stopped by righteousness. | Micro-biology | Most diseases are caused by germs and can be stopped by soap. |

| Earthquakes are caused by the wrath of God. | Geology | Earthquakes are caused by plate tectonics due to magma convection. |

| Eclipses of the sun are a sign from God. | Astronomy | Eclipses of the sun are just the moon obscuring our view of the sun. |

| God intelligently designed and placed all of the complex life on this Earth. | Evolutionary Biology | Complex life evolved from simpler life on this Earth. |

| The Earth was created about 6000 years ago. | Radiology | The Earth accreted about 4.5 billion years ago. |

| The heart is responsible for emotions and feelings. | Cardiology | The heart pumps blood. The brain is responsible for emotions. |

| Consciousness is implemented in a spirit. | Neuroscience | Consciousness is implemented by the brain. |

| Feelings that confirm what we choose to believe are a witness of truth from the Holy Spirit. | Psychology | Feelings that confirm what we choose to believe are a natural bias that people in all religions share. |

Explosion analogy

The explosion analogy is an attempt to illustrate the statistical improbability of complex things spontaneously forming. It can take many forms, including:

- "If an explosion occurred in a print shop, would the complete works of William Shakespeare just fall together?"

- "If an explosion occurred in a clock shop, would a working clock happen to self-assemble?"

- "If an explosion occurred in a junkyard, would a Mercedes Benz spontaneously form?"

The "explosion" is usually intended to represent the Big Bang, and the complex product represents life. Thus, the explosion analogy suggests that life would not be expected to occur following the Big Bang without an intelligent designer.

The implied connection between the Big Bang and abiogenesis reflects ignorance of the fact that the Big Bang is not a theory for explaining the origins of life. The Big Bang is a theory for explaining the observable expansion of the visible Universe, and is believed to have occurred more than 13.7B years ago. By contrast, abiogenesis is an unrelated theory for explaining the origins of life on this planet, and is believed to have occurred less than 4.6B years ago. The two theorized events are separated by a gap of more than 9.1B years, spanning about 2/3 of the time since the Big Bang.

If the bad explosion analogy is omitted, the remainder is the Improbability argument.

Faith argument

The faith argument sounds like this: "Faith is such a small price to pay. All that is required from you in exchange for the gift of mercy that will enable you to attain incomprehensible glory for all eternity is that you have faith in God. How arrogant to refuse such a simple thing! God has given you life and a family and an Earth on which to live. He has given you everything! Will you not even express a modicum of gratitude by having a little faith?"

The first thing that should be immediately obvious when the faith argument is made is that someone really really really wants you to have faith in God. The deal has been sweetened as far as any deal can possibly be sweetened: If you just give them what they want, you will receive an eternal and unending reward of unimaginable bliss! And if appealing to your sense of greed doesn't sway you, they resort to an emotional plea: You would be a horrible ungrateful person for rejecting the most sincere act of sacrifice ever offered if you don't accept the deal! And if that doesn't move you, they will try to appeal to your need for personal acceptance and sense of belonging: Someone understands you, cares about you personally, accepts you, and loves you almost unconditionally, as long as you just have faith!

But who exactly wants you to have faith? And why do they want you to have faith so badly? Let us consider both the believers' and unbelievers' answers to these questions:

Believers' version: God is the one who wants you to have faith. The reason he wants you to have faith is for your own good. Because God respects your free will, he will not force you to believe. (See also the free will argument.) But if you believe, then he can take care of every other deficiency in your character and make you into a glorious being. And when Christian religious denominations plead with you to have faith, they are only supporting God's will for your personal well-being.

Unbelievers' version: Religion is the entity that wants you to have faith. The reason it wants you to have faith is because faith is what sustains the religion. If a religion were to lose all of its believers, it would be a dead religion. Just as corporations work to maximize profit, politicians work to improve their popularity, and universities work to establish credibility, so religions work to promote faith.

Perhaps, one of the best ways to discern which of these two explanations is more plausible is to simply try to understand them both. It is very difficult to comprehend why God is interested so particularly in faith, and not so much in other attributes that help a person to learn, such as interest in learning, humility, willingness to work hard, resiliency to defeat, or curiosity. It is also very difficult to comprehend the supposed relationship between free will and having faith. See also choice argument. Ultimately, it is not at all clear why God needs faith. But it is very easy to see why religions need faith.

Faith in science

Sometimes theists point out that science requires faith. The legitimacy of this claim depends entirely on how one defines "faith". There are some definitions of faith for which this statement is true, and many for which it is not.

Sometimes faith is defined simply as "trust". No scientist has time to repeat all of the experiments that all other scientists have performed. Consequently, scientists operate with trust that other scientists actually performed the experiments they report to have performed, and actually obtained the results they report to have obtained. This trust has been violated in several notable cases, such as:

- The Piltdown Man,

- The Tasaday Tribe, and

- The Cardiff Giant.

Because faith has many conflicting definitions, it can be dangerous to admit that scientists have "faith", because someone will inevitably interpret the statement using a different definition of the word. Another common definition of faith is, the choice to accept or believe in something without having any verifiable evidence. By this definition, faith is directly opposed to the scientific method. The following thought experiment illustrates some of the issues with this definition of faith:

Suppose Alice asks Bob to consider a new idea. Bob might choose to trust in Alice by evaluating her new idea. His choice to tentatively accept her idea without proof, so that he might give the idea due consideration, might be called a type of faith. Alternatively, Bob might tell Alice that he that he has faith in his existing beliefs, and is therefore unwilling to consider her new idea. This is also a type of faith, even though the attitudes are almost completely opposite! The primary difference is the object of the faith. In the first case, Bob put his faith in Alice. In the second case, he put his faith in himself, or perhaps in the original source of his beliefs.

It would be completely ambiguous to refer to one of Bob's two potential choices as "faith" and the other as "doubt". If Bob exhibits "faith" in Alice, that implies a degree of uncertainty about his existing beliefs, and if he exhibits faith in his existing beliefs, that implies a degree of distrust toward Alice. Thus, one cannot just choose to "have more faith". One can only choose to exercise faith in something, and in that act chooses to exercise doubt in the opposing direction.

One might ask, would it be good for Bob to exercise faith in Alice? Ultimately, the answer depends on whether or not Alice's new idea is right. However, proof of the correctness of Alice's idea is probably not available, or else there would be no call for Bob to exercise faith in it at all. Therefore, Bob must make his choice without knowing the answer. In general, tentative trust leads to greater productivity. Thus, good faith tends to be that which is motivated by humility, open-mindedness, optimism, curiosity, and temporary trust. bad faith tends to be that which is motivated by pride, closed-mindedness, pessimism, superstition, and permanent dogmatism.

Many people assume that "faith" implies "faith in God", and therefore lazily omit specifying the object when they talk about faith. Such sloppy communication has a negative effect for those who do not believe in God because it implies that they are unable to extend trust. It is even more exclusionary to refer to one's set of beliefs as one's "faith". Other definitions of faith, such as "the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen", tend to be more confusing than helpful.

Faith healings

Mark 16:17-18 records that Jesus identified several signs that will follow those who believe:

And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues;

They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.

Several Christian denominations, therefore, engage in practices that attempt to manifest these signs through miraculous healings.

Due to the often-surprising power of the placebo effect, some minor medical conditions actually seem to benefit from faith healings, and due to the prevalence of confirmation bias, those who witness faith healings are often prone to become convinced that the performance exhibits genuine power from God. However, despite the widespread practice of faith healings, they continue to elude empirical statistical validation. Many faith healings have been exposed as pious frauds. Atheists often note that no amputee has ever been healed by faith, because that would be something that could be documented and verified, and if the intentions of faith healers were really to help people, rather than just to promote their religion, then they would perform service-healings at hospitals instead of in religious meetings.

False dichotomy

In the context of theism versus atheism, a false dichotomy usually takes the following form:

- If there were no God, then [some absurd condition].

- Obviously [some absurd condition] cannot be true.

- Therefore, there must be a God.

If the absurd condition does not obviously follow from the non-existence of God, then additional argumentation is needed to show that no other condition would be possible. Some commonly leveraged conditions that do not follow from the non-existence of God include:

- A complete lack of matter or energy

- A complete lack of order

- A complete lack of life

- A complete lack of knowledge or science

- A complete lack of both religion and atheists

- A complete lack of consciousness

- A complete inability of people to find morality

- A complete inability of people to find meaning or purpose in life

Fine-tuning argument

The fine-tuning argument is an attempt to prove the existence of God. It is usually presented as follows:

- Life-as-we-know-it would not be possible if certain physical constants differed by even extremely small amounts.

- Therefore these constants must have been fine-tuned by someone.

- Whoever did that, we shall call "God".

The fine-tuning argument is a type of God-of-the-gaps argument. That is, there is something science cannot explain, so the correct explanation must be God. However, there are many reasons why one might be justifiably skeptical that God is, in fact, the correct explanation for such specific physical constants:

- Many God-of-the-gaps arguments have been made for various unexplained phenomena in the past. As science advanced and explanations were found, the correct one has never yet turned out to require something supernatural.

- The proposed solution is no better than the problem. That is, God is no less complex, no less well-calibrated, and no less difficult to comprehend than the physical constants. The fine-tuning argument is often presented with numbers that include a very large number of zeros. But if one tried to describe the power of God or the number of bits of information in his knowledge with those same numbers, theists would generally balk and say, "there are not nearly enough zeros".

- We do not yet know how representative life-as-we-know-it is of life-in-general. It may be that some form of life would occur with different physical constants, and life-as-we-know-it is just a byproduct of arbitrary constants.

- The vast majority of the known Universe is not actually habitable. Thus, one might turn the argument around by asking why the Universe was not better-designed for supporting life. Interestingly, the ratio of potentially habitable regions in the known Universe to uninhabitable regions is even smaller than some of the physical constants used to make the fine-tuning argument.

- Some of the physical "constants" used to make the fine-tuning argument may not actually be constant across the whole Universe. As one example, the Cosmological constant is definitely known to not be constant in different regions of the visible Universe. One would naturally expect life to pop up only where the constants were suitable for life, and that may be why those constants appear so finely "tuned" around us. This possible explanation invalidates the second point of the fine-tuning argument because it shows that the constants are not necessarily fine-tuned, and it also negates the third point because it does not even vaguely resemble what people generally mean when they use the term "God".

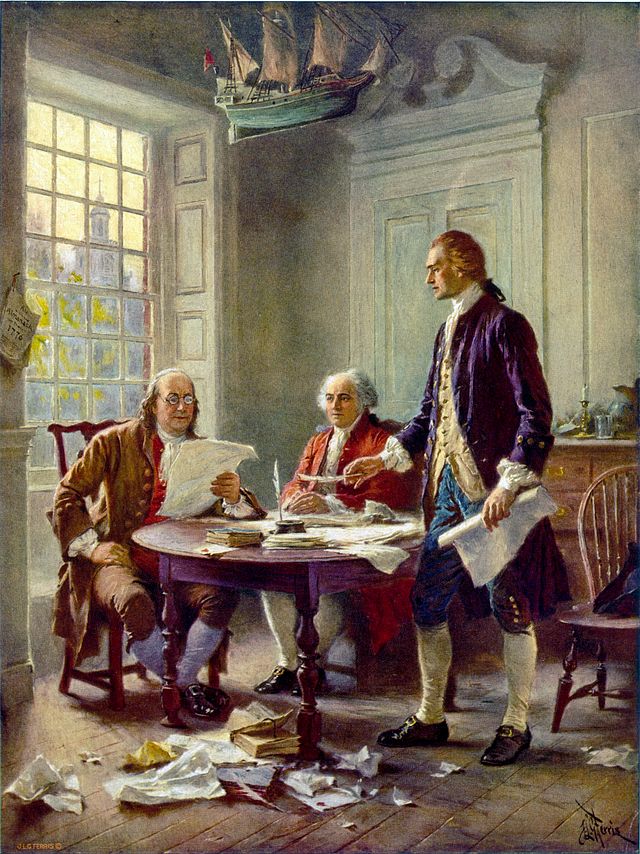

Founding fathers arguments

Many Christians in the United States revere the founding fathers of the United States (with some very good reasons). However, sometimes they use the founding fathers to make such claims as: "The founding fathers were all Christians", or "the founding fathers intended for the United States to be a Christian nation."

It is certainly true that most of the founding fathers were Christians. However, given the time period, a surprising many of them were actually deists. (Deism is the position that God created the Earth and life, but it rejects the idea of a personal God who intervenes in the affairs of humans.) In the 1700's, science had not yet discovered any complete natural explanations for the organization of the Earth or the existence of complex life on it. Consequently, deism represented what was the most intellectual and rational explanation that was then available.

The assertion that the founding fathers intended for the United States to be a Christian nation is easily refuted. The Constitution of the United States makes only two references to religion, and only for the purpose of clarifying that it should be separated from politics. Sometimes Christians refer to the Declaration of Independence, which does include statements that offer deference to a Creator, but the Declaration of Independence was not established for the purpose of setting precedent for the establishment of the nation, as the Constitution was. The other writings of the founding fathers explicitly describe that they were deliberate in creating a wall of separation between church and state, so it was obviously not merely an oversight that they failed to mention Christianity in the Constitution. Moreover, history indicates that the founding fathers were deliberately trying to avoid some of the problems that occur when politics and religion were mixed, such as the debacle in which Henry the Eighth established the Church of England.

Sometimes, the motto "in God we trust" as printed on U.S. money, or the "under God" clause from the Pledge of Allegiance, are cited to suggest that the United States is a Christian nation. However, both of those were added in the 1950's, and do not represent the diversity of views that exist within the United States.

Since the Founding Fathers of the United States were a diverse group with many differing opinions, it is certainly possible that some of them actually did intend for the United States to be a Christian nation. However, the wishes of some of the Founding Fathers neither establish the direction for the nation nor even necessarily represent what is good or right.

Free will argument

The free will argument is a standard Christian response to question like, "Why does God allow evil to exist?" The free will argument responds by saying, "God will not interfere with free will." In this exchange, the atheist is implying that there is something negligent about God having unlimited power and operating in a position of authority over the world while doing little to interfere with the problems around us. By invoking "free will", the theist is essentially responding that God has a higher purpose in refraining from taking any action. It is closely related to the mysterious ways justification and the postmortem compensation justification.

The problem with the free will argument is that it implies evil is necessarily the consequence of sinful choices. Many horrific crimes are committed by people who sincerely believe they are supporting the will of God. Even when the perpetrators are only negligently guilty of failing to discern the evil behind their actions, there are cases when large numbers of innocent victims must suffer against their own wills for the choices of a few misguided individuals. Thus, the inaction of God is not maximizing free will, as is claimed, but is ensuring jungle rule.

Fruits, knowing them by

Matthew 7:16 records that Jesus described a method for discerning false prophets, "Ye shall know them by their fruits". This line is sometimes flung at atheists to suggest that the fruits of religion are sufficient basis to believe, and that religion teaches people to be moral, while atheism deprives people of a basis for morality.

This argument reduces to a form of the morality argument, and makes the same fallacy of assuming that belief in God is required for morality. Moreover, upon closer inspection, the "fruits" of religion are not quite the fresh produce that is often assumed: While religious denominations teach their individual members to love their neighbors, the high-level reputation of religion is still one of intolerance and hypocrisy. And while religious denominations certainly teach their individual members to repent of all their sins, the high-level reputation of religion is one of never acknowledging any wrong-doing, and stubbornly refusing to acknowledge new evidence or make any meaningful changes in its teachings or practices.

Further, religion is not the only entity capable of bearing fruit. Science is made of scientists who dedicate tremendous time and effort toward making positive impacts in the world. The fruits of science include real advances in the domain of knowledge. Religion may claim to receive revelations from God about supernatural concepts, but its supposed contributions to knowledge cannot be verified. By contrast, science is responsible for every advancement in technology, and can claim such fruits as modern sanitation, electricity, computers, the Internet, smart phones, and modern medical procedures. Religious apologists often make the religious scientists argument in attempt to take credit for these fruits, but it is ultimately the methods of science and not religion that produced the fruit, and the scientific method works just as effectively for both believers and unbelievers.

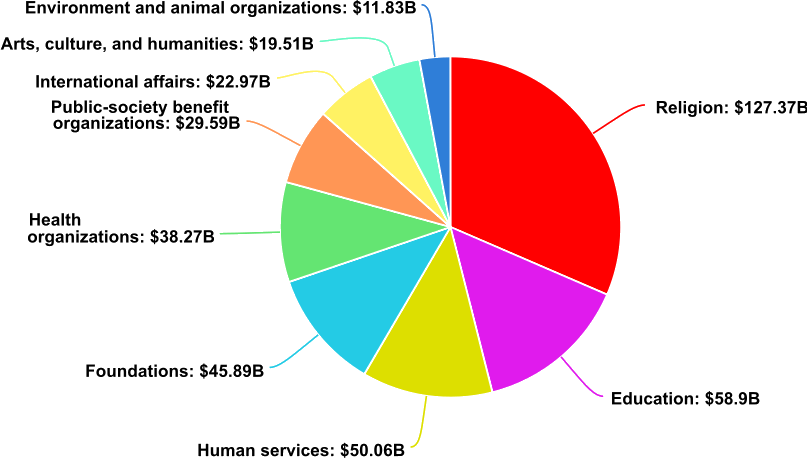

The chart below shows the distribution of charitable giving in the United States in 2017 according to http://givingusa.org:

More than twice as much money was donated to religion than to any of the other categories, and religions in the United States tend to focus much more on producing faith than on producing works. Religion also has a strong effect for making people skeptical toward science, and thus tends to discourage giving for fundamental research, which tends to have the greatest long-term benefit. Notably, donations toward fundamental research were not even significant enough to warrant their own category. A pessimistic perspective might observe that because of religion far more money is invested in attempt to interfere with the advancement of verifiable knowledge than to promote it.

Gaps in the fossil record

Gaps in the fossil record are often cited as evidence that evolution is not true. Here is an example meme used to make this point:

This claim falsely assumes that evolution predicts there would not be gaps in the fossil record. Counter to popular intuition, most dead creatures do not form into fossils, and evolution does not progress at a constant or even steady rate. The combination of these two factors naturally results in fossils that are clustered around certain species with very few intermediate remnants.

Why do very few dead creatures actually become fossils? Because highly specific conditions are necessary for the fossilization process to even begin. The vast majority of creatures either decompose or are eaten by other creatures before leaving any permanent trace.

Why does evolution happen in unsteady spurts? When the mutation of only one particular nucleotide in a sequence of DNA leads to a selective advantage, nature can find it very rapidly. However, this typically leads to local optima where a large population of a particular specie may form. In order to break out of a local optimum, an unlikely combination of mutations may be required, which can take orders of magnitude longer to occur in nature. When that finally happens, evolution proceeds rapidly again until it finds the next local optimum. This sporadic behavior can be easily confirmed by plotting fitness with respect to generations in a genetic algorithm.

Moreover, even if evolution did predict that there would be a continuous fossil record, the claim that there are big gaps is debatable. Even among creatures that are still living, enough intermediate stages are represented to form an apparent spectrum of continuity. If scientists were to divide the size of every gap in half by finding an intermediate fossil, opponents of evolution would likely still be dissatisfied with the span of the remaining gaps because subjective evaluations are not very effective for convincing someone who is already determined to arrive at a particular conclusion. So, are the gaps really unreasonably large? It depends who you ask. In general, those with more knowledge on the subject are also more likely to agree that the existing amount of evidence is already very convincing.

(It should also be noted that the meme shown above also makes several factual errors in addition to its claim about gaps in the fossil record: For example, the number of chimpanzees has already declined to fewer than 300K, the number of humans has grown to more than 7B, and humans did not evolve directly from chimpanzees, but from a common ancestor that they both share.)

Gish gallop

See Laundry list of arguments.

God-of-the-gaps argument

A God-of-the-gaps argument is one that claims God must be responsible for something that science cannot yet explain. One of many possible examples includes:

- Science tells us the Universe started with a Big Bang.

- Science does not know why the Big Bang occurred.

- Therefore God is responsible for it.

Such arguments can be difficult to refute because the correct explanation for the phenomenon is not yet known. Many God-of-the-gaps arguments have been made for various unexplained phenomena in the past, but as science has found explanations, the correct one has never yet turned out to require something supernatural. For example, God was once believed to live on the tops of mountains. After those regions were explored, he was believed to live in the clouds. When the sky was explored, he was believed to live in some supernaturally unreachable place. Diseases were once believed to be caused by evil demons. Now, we almost universally accept that they are caused mostly by germs.

Neil deGrasse Tyson famously pointed out that God-of-the-gaps arguments imply that "God is an ever-receding pocket of scientific ignorance that's getting smaller and smaller and smaller as time goes on".

Good effects of religion

Some studies have correlated belief in God with positive effects, such as reporting greater satisfaction in life, lower incidence of gambling and drug use, lower incidence of suicide, and longer average life span.

However, it is important not to confuse being good with being true. If religions only claimed to offer moral guidance or wisdom, then being good would be sufficient for them to deliver what they claimed. But many religions claim to know that God is real, that we will live again after we die, or that an eternal reward in heaven awaits believers. These are factual claims. Religion that make factual claims need to do more than just be good. They also need to be true.

Not everything that makes people feel good is necessarily ultimately good. For example, habit-forming drugs may seem very beneficial at first, but can have devastating long-term effects, especially on those who overuse them. If a religion seems to be good, but is not actually true, it may do more damage in the long term, especially if it is successful at persuading people to entirely immerse themselves in it.

An oft-cited example of something positive religion does is give people a sense of purpose in life. When people believe they will be rewarded in the next life for good behavior, it is easier to do good without entirely giving up egocentric tendencies. But is this ultimately as beneficial as it seems? On the one hand, it is often effective at geting positive results quickly. But on the other hand, it creates an unnecessary dependency. If the believer ever loses faith, he will also lose his reason for being moral along with it. One might ask, wouldn't it be better for people to take the more difficult path of learning not to be egocentric in the first place? (See also purpose of life.)

Perhaps some shallow individuals are actually better off being taught lies that keep them from engaging in irresponsible behaviors. However, the effects that these people have in raising children and influencing others should not be ignored in the assessment. Others also exist who hunger for real truth, and will only find morality in explanations that can be supported with evidence. Perhaps, people have grown complacent by evolving with religion for too long, but the time has come to move toward finding real purpose founded upon an accurate representation of reality.

Ignorance, argument from

An argument from ignorance sounds something like this:

- There are things I do not understand about science.

- ...so it must be wrong,

- ...and God must be the correct explanation.

Arguments from ignorance attempt to get the opponent to jump on the "bandwagon" of dismissing science. But usually they just expose ignorance.

Improbability argument

The Improbability argument suggests that it is statistically improbable for even primitive life to have spontaneously formed. (It differs from the Complexity argument, which uses complexity to dismiss evolution rather than abiogenesis. Note that the two arguments are often made together by using complexity to dismiss both abiogenesis and evolution.) The improbability argument is typically presented with the following supporting details:

- Even the simplest single-celled life form on Earth still contains significant complexity.

- The statistical probability of so much complexity spontaneously coming together is extremely small.

- Therefore, abiogenesis requires an intelligent designer.

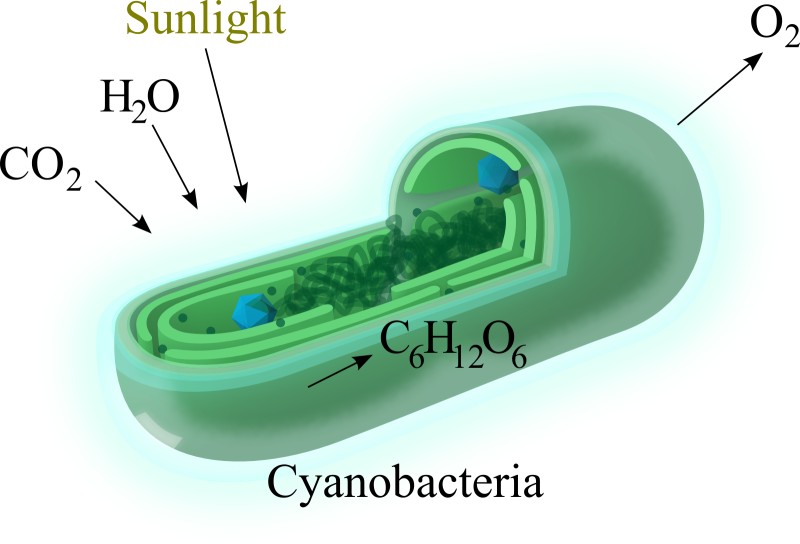

The primary error of the improbability argument is its assumption that the simplest modern biological life is representative of early pre-life. By modern definitions, "life" requires a number of complex features, such as cellular walls. Consequently, simple chemical reaction, such as fire, are not regarded as being "alive". However, nature is not constrained by modern definitions of life. Whatever spontaneously formed more than 4 billion years ago probably met only a small subset of modern requirements for life, and important features like cellular encapsulation, photosynthesis, or the Krebbs cycle probably evolved later.

The plausibility that pre-life may have been little more than a simple chemical reaction can be seen by noting how many properties of "life" are satisfied by fire, a simple chemical reaction that most people are familiar with:

- Fire consumes food (fuel),

- it emits waste (smoke),

- it generates heat,

- it grows and propagates,

- and it can die.

Although fire is not technically alive, it exhibits several of the properties of life, and it spontaneously occurs in nature. The fact that no simple chemical reaction has been continuously reacting for 4 billion years indicates there is a significant survival advantage for reactions with cellular encapsulation, so natural selection would apply just as well with pre-life as it does with modern life.

Another possible resolution for the improbability argument is massive parallelism. The oceans are very big, especially relative to a microscopic organism, and abiogenesis only needed to occur once in order for the Earth to now be covered with life. Moreover, the number of planets estimated to be in the Milky Way galaxy is estimated to be at least in the hundreds of billions, and the number of galaxies in the Observable Universe is estimated to be at least in the trillions, and the portion of the whole Universe occupied by the Observable Universe is entirely unknown. It may be that much of the Universe is actually mostly lacking in life, and Earth just happens to have been a place where a highly improbable event occurred. After all, if abiogenesis happened to occur anywhere at all, those places would be the only places where life would exist to wonder why it happened there.

Incredulity, argument from

An argument from incredulity basically says, "God must exist because nothing else makes sense." Generally, it is used as a lazy summary of some other argument. For example, instead of making the complexity argument, one might simply express, "You think intelligent humans evolved from unintelligent primates? Really? That's stupid." However, arguments from incredulity generally say more about what a person doesn't understand and only serve to weaken their position.

Irreducible complexity

Irreducible complexity arguments suggest that certain complex features of advanced life forms could not have evolved due to natural selection because there are no intermediate steps that would offer the creature any advantage. For example, why would birds evolve wings if shorter wings would not be sufficient to enable them to fly?

This fallacy of this argument is more apparent if it is restated as follows:

- Complex features exist.

- I cannot think of any advantageous intermediate stages for evolving such complex features.

- Therefore no advantageous intermediate stages are possible.

Although the person making the argument may be very intelligent, evolution has the significant advantages of utilizing a large population that effectively explores the complex space of possible mutations in parallel and of operating over counter-intuitively long durations of time. Historically, many supposed instances of irreducible complexity have later turned out to have incrementally progressive pathways that were followed by evolution. For example, flightless birds are known to exist, and they use their wings for a variety of alternate purposes including limiting the impact of falls, sheltering offspring, and regulating their body temperatures.

Joystick hypothesis

The joystick hypothesis suggests that the brain is a sort of joystick or complex control paddle that a spirit uses to control human bodies. It gives a role for the brain while simultaneously claiming that supernatural spirits are actually responsible for thinking and consciousness.

If the joystick hypothesis were true, then the brain would be an interface between the physical realm and the spiritual realm. However, neuroscientists can measure and stimulate the activation responses at the level of individual neurons. Their spiking patterns have been shown to respond deterministically to the stimulus they receive from their dendritic connections. Hence, any influence from a supernatural spirit would have to be so small as to avoid detection. And if the influence from the spirit is so subtle and small, then its role in directing consciousness is diminished and the brain is again responsible for our consciousness.

One cannot make a car move faster by cracking open the dashboard and forcing the speedometer to indicate a higher speed. Similarly, if the brain played only a passive role in consciousness, then doping it with chemicals would not be expected to have lasting influences on consciousness. Yet, people who are put under anesthesia do not wake up with memories of being unable to reach their bodies. They wake up with no memories at all, because the organ responsible for consciousness has been chemically inhibited.

Judgment argument

A question many theists seem to enjoy asking is, "How will you feel on the day of judgment when you have to face God and admit that you didn't believe?"

Implicit in this question is the assumption that there is something fundamentally wrong with not believing in God. However, the primary choice involved in belief is whether or not to be honest about the evidence one has observed. So the simplest answer that a typical atheist might give is, "Honest". Surely, the God of truth would not be more pleased with people who engage in self-deceit in some kind of attempt to secure an eternal reward.

Some atheists might even sincerely hope for an opportunity to face God again, if he actually turns out to be real. As one atheist put it, "It would be nice to finally be judged by someone who actually understood me, and who might know what I went through to remain true to what I believed."

See also Pascal's wager.

Kalam cosmological argument

The Kalam cosmological argument was formalized by William Lane Craig. It is a particular case of cosmological arguments. It states:

- Everything that began to exist had a cause.

- The Universe began to exist.

- Therefore the Universe had a cause.

It should be clarified that the Kalam cosmological argument is not an argument for God. It is an argument for a cause. Unfortunately, many atheists fall into the habit of opposing any position theists assert. Consequently, this argument often dupes atheists into taking indefensible positions. Sometimes, a better approach is just to admit that it might be right. After all, the gap between its actual conclusion (a cause) and God is really its greatest deficiency as an argument for the existence of God.

It is sometimes argued that any cause of the Universe must necessarily be outside of the Universe. But this argument hinges on having a very precise definition for Universe at a time and place where nothing is known. So it is essentially an attempt to define God into existence. The actual difference between things that are "supernatural" and things that are "natural"-but-not-yet-understood is really a useless distinction since by definition neither is yet understood. But an honest truth-seeker must be careful not to deceive himself with his own bias by jumping to the conclusion that an original "cause" must have properties he prefers without basis.

Since the two premises are not definitely wrong, it is inadviseable to take a strong position against them. But it is easy to refute any claims that they are self-evidently right: