Treating Infections of Dangerous Memes

By: Mike GashlerIn 2007, Dan Dennett delivered a TED talk called Dangerous Memes, in which he characterized certain religious beliefs as parasitic memes that had evolved to hijack human minds, and drive their hosts to do things that sustain the life of the parasite. Here's a link to the talk:

Of course, it's one thing to know how to identify a serious condition, and quite another to figure out how to treat it. We all know people we care about who have been infected by dangerous memes. So what can we do to help them?

Let me be up front that this is not a 3-easy-steps-to-rescue-your-loved-one kind of article. It is more of a let's-analyze-the-tar-out-of-this-problem kind of article. So if this is a problem you care about enough to do some studying, then keep reading. There really are effective things you can do. But effective doesn't necessarily mean fast.

If you were once the victim of a dangerous meme, or if there is someone specific you care about who is currently afflicted by a cognitive parasite, then you probably already understand how challenging this problem is. The solutions are not going to be quick or easy. But it is not an incurable problem either. Millions of people have escaped the clutches of dangerous memes, and an increasing large portion of the population seems to be inoculated against some of the more virulent strains. So without further ado, let's put this problem under a microscope.

About the evolution of understanding

In biological evolution, we can observe that primitive creatures tend to respond reflexively to sensory stimuli. For example, you can build a remote-controlled cockroach by simply plugging small wires directly into its antennae and sending signals that mimic what the antennae send. (This is not sci-fi. There are real DIY kits available for hijacking cockroach minds.) By contrast, human minds are not so easily tricked. If you put a virtual reality headset on a human, he will likely be amused for a while, but will eventually say, "I have some real obligations", will take it back off, and will hurry off to attend to some other obligation.

The difference is that humans have large and well-developed cerebrums. (The cerebrum is the big wrinkly layer of neurons covering the surface of your two brain hemispheres.) It's the part of your brain that enables you to comprehend what's going on in the world, rather than just reflexively respond to immediate conditions. It's what gives you awareness and makes you a conscious being, as opposed to a robot-like drone. The cerebrum is what empowers a human wearing the virtual reality headset to understand that he was temporarily operating in a hypothetical world. He could enjoy the world it presented to him, but he always knew it wasn't real.

If we analyze the brains of creatures at various stages of evolutionary development, we can see that nature's initial solution was for creatures to act reflexively. The cerebrum didn't develop until about 200M years ago. To put that into perspective, that's only about 5% of the time life has been on the Earth. To compare that to a year, if life appeared on January 1, and today is December 31, then creatures on this Earth have had cerebrums to enable them to understand what they were actually doing since about Dec. 12.

(Just to be clear, this doesn't mean it's cool to go around torturing bugs, or lobsters, or other creatures that lack cerebrums. Even such primitive creatures probably still have some degree of capability for awareness distributed throughout their brains. It just hasn't consolidated into a distinct organ dedicated for the task, like it has in mammals. When it comes to life, almost nothing is ever a binary "on"-or-"off" concept. Almost everything turns out to be some sort of continuum that has only mostly evolved into distinctly cluster-able concepts. And besides, violence has negative effects for the perpetrator too. So, don't even torture robots. It's just not a nice way to behave.)

Why is it important to understand a problem before we try to fix it? Can't we we just try stuff until we stumble across something that works? Sure, that might work for simple problems. But the problem we aim to fix is not a simple problem. If you just rush out and try to fix this problem, you will probably make it worse. Take the time to understand this problem, so you can do it right.

The capability for understanding gives creatures a powerful evolutionary advantage. (Hopefully this is stupidly obvious.) Cheetahs are fast, but humans drive cars much faster than cheetahs can run. And humans can maintain that speed over distances that would leave the cheetah dead. Birds can fly high, but humans fly much higher. And humans can do it while carrying much heavier payloads. Bears are strong and certainly have scary claws. But a man with a gun is far more deadly. And which creatures have built nuclear weapons, traveled through space, built hospitals, Universities, or the Internet, and carry cell phones? What a huge difference it can make to take the time to really understand things!

And that is why you need to take the time to really understand this problem before you rush out and try to fix it. It is not a simple problem. It is one that is riddled with counter-intuitive intricacies. And it is one that requires surgical precision to address, not passionate emotion-driven brute force.

The modularization of knowledge and wisdom

Biology is not the only domain where we have seen this pattern of first reacting reflexively, then subsequently learning how to understand the problems being faced. The field of artificial intelligence also evolved in a similar manner.

The first software agents to be developed were reflex agents, built with hard-coded logic to respond directly to their immediate perceptions. But as the field matured, a new sub-discipline called machine learning emerged. Machine learning focuses on the supporting task of gaining understanding. It consumes data and builds models that provide understanding of the world that produced the data. In other words, earlier instantiations of AI only looked forward, but machine learning looks back. Machine learning seeks to learn from the past, and the knowledge it discovers can serve as a basis for the other components of artificial intelligence to plan for the future.

This new learning-based approach was a tremendous boon for artificial intelligence. It provided the missing component of knowledge that informed the planning components so they could make wiser choices. And that led to the much more intelligent AI algorithms we have today.

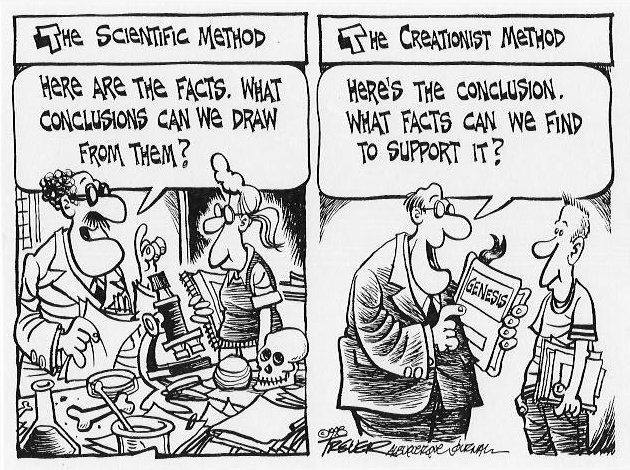

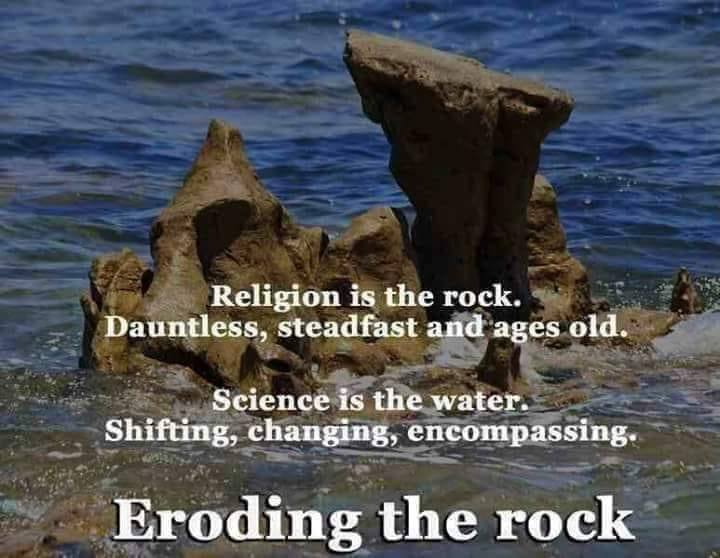

And those are not the only two times this modularization of learning and planning has occurred. Yet again, we can find a similar pattern in society itself. For millennia, society was directed to a large extent by religion. The Earth's many religions strived to provide people with wisdom, by telling them what choices they should make. But they all did so to a large extent without much of a foundation in knowledge. Then starting around the 14th century, the Rennaissance occurred. People began seeking knowledge for knowledge's sake. Science transformed from a curiosity to a recognized discipline. And society itself started to possess an important component of intelligence that was previously missing--knowledge.

In light of these patterns, let us consider what we can learn about these dangerous memes. It certainly appears to be natural for there to be separate components for pursuing knowledge and wisdom. And we find precisely that kind of separation between the domains of science and religion. But it also appears from these patterns that the wisdom component is supposed to be informed and empowered by the knowledge-seeking component. That does not seem to be the case in modern society. What is happening?

Sometimes, science advocates take the position that science and religions are mortal enemies--that two will enter the battle arena, but only one can emerge victorious. And on the other hand, religions frequently take the position of claiming that they are fully compatible with science. Yet while saying this, they encourage their adherents to immediately reject any teachings that challenge their authority, and strongly discourage anyone from using science as a basis for informing their decisions. But neither of these positions is consistent with the pattern we find in biology, or artificial intelligence, or the evolution of society itself.

These patterns leads us to the eye-opening realization that the issue of religion is somewhat more complex than a simple case of a parasitic infection. It appears that society may be trying to modularize its knowledge and its wisdom. If that is the case, then perhaps there is a legitimate role for religion to play in a well-functioning society. And yet, how terrible that this role is currently being filled by something that systematically rejects scientific knowledge, and even fights to suppress it--something so prideful as to create it's own false version of knowledge and attempt to superimpose it on top of science to drive its adherents to sustain its life cycle!

My hypothesis on the matter is that the transition started in the Renaissance has not yet finished. Sometimes evolutionary time-scales can seem frustratingly slow. I don't know what exactly a healthy religion will look like in the distant future after the process converges, but I am confident that a healthy religion would build on scientific knowledge rather than attempt to ignore it, dismiss it, or claim to have some proprietary method for knowing unsubstantiated facts beyond science's purview. Alas, we don't get to live in that future. So let us consider how this perspective might direct our attempts to deal with our present circumstances, and possibly help this awkward transition to happen a little faster.

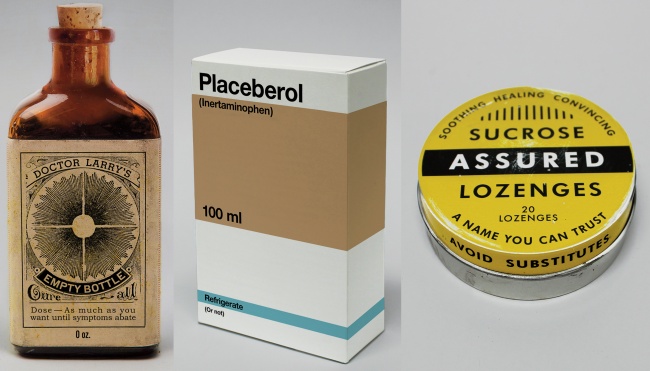

Imagine finding a hungry young child eating candy, and telling the child that candy is unhealthy. If you succeed at convincing the child to stop the unhealthy practice, but do nothing to fill the child's hunger, all you have accomplished is to frustrate child and postpone her inevitable return to the candy when the hunger grows.

Or imagine finding a person struggling with depression self-medicating with recreational drugs. Imagine telling that person that he is bad for abusing addictive chemicals. You might think that you are doing something good or helpful. But if you have neglected to identify and address the underlying motivation, then what have you really accomplished? You have made a depressed person feel bad person for his behavior. You may have temporarily prevented him from abusing drugs, but when his depression returns with more force, he will do it again with greater shame, and this will further aggravate the depression that has been driving the addition.

Actions speak louder than words

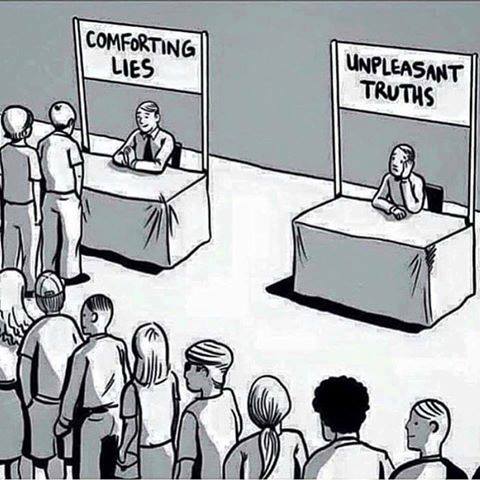

So telling people "religion is bad" is not the answer. Calling it a crutch, or telling people they are weak or ignorant for needing it doesn't do much good either. At some level religious people understand that the concept of religion has potential to be a positive thing, and they often see it for what it could be, rather than what it is. So when you say those things, what do they really hear?

You know there is lots of evidence to support your position. But does the person you are speaking to know that? Nope. And even if they do know about it at some subconscious level, they are probably not trying very hard to see you as a reasonable person while you attack what is important to them. Rather, they are going to assume that you are being dogmatic.

What they hear is, "It's cool to be dogmatic. It's okay to be stubborn. It's okay to claim to know things without presenting any supporting evidence. And it's cool to let your feelings drive you to overconfidence in your position."

That is not the message you want to be giving! That is the problems you want to solve, not exacerbate! How do you say something so that the same message will be heard?

The answer is, your actions must consistently match your words.

That's not something natural or easy to pull off. So let's discuss some critical habits that will help you deliver your message while behaving the way you want the other person to behave.

Identify reasons to support every claim you make. If you don't have a supporting reason, don't claim it. This habit makes communicating much more difficult. It is a lot of work to do. And it makes each of your statements vulnerable. It basically hands the other person something they can potentially question, doubt, or attack with every statement. But think of that as the price for having a meaningful conversation. When you are careful to always identify reasons, you set a tone for the conversation that says, "We are talking about reality now, and not the fervency of your convictions". After all, that's what you want them to do, right? Well then, that means you have to do it. Every time you assert something without identifying a reason, you sabotage the attitude that you want from the other person.

If you say, "evolution is an established fact", your words may have expressed something valid, but your action was to appeal to authority. That's bad. The other person will naturally respond by appealing to their own source of authority, which they probably consider to be higher than yours. By contrast, if you say, "evolution is the best explanation I know for creatures sharing gene sequences", it may seem weaker to you, but it's really a much stronger position. The other person's natural response will be to seek for reasons why you are mistaken. Talking about reasons is a good. If the other person presents something you can learn from, then learn from it. Use your actions to show that learning is more important to you than teaching. (If that is not true, then you are the one who needs to change first.)

Find a way to be humble. Just so there is no misunderstanding here, I did not just say, "be ready to be humble in case the other person makes a good point". What I said was, "Find a way to be humble". That means you have to listen to the other person. And moreover, it means you have to exert some real effort to dig through their piles of crap to find something you can learn from. Seriously.

Why do you have to do that? Because its what you are asking them to do. Remember from their perspective what you are offering is a pile of crap. People have an inherent tendency to respond in kind to the way they are treated. So the fastest way to get someone to start operating at a higher level is to demonstrate it, to do it first, and just keep doing it until they start doing it too. So, if you want them to take you seriously, you have to invest time into taking them seriously. It's the price of having influence.

Unfortunately, this principle operates in both directions. The person you are trying to reach certainly thinks he or she is right and you are wrong. So he or she will be more interested in changing you than changing him or herself. That's the way it is, and you've gotta just accept it. When you recognize that they are preaching, but never genuinely listening, you will feel tremendous pressure to respond in kind. You must not let that happen. Imagine two people shouting at each other, both with their ears plugged. It's useless. It's demoralizing. It's a big waste of time. Do not let that happen. Stubbornly refuse to become stubborn. You must trust that your example will eventually wear the other person down. It will probably take much longer than you would prefer, but it does work. Your example is the most powerful influencing force you have to work with--much much more powerful than your words.

Don't have just one position. If 85% of the evidence supports position A, and 15% of the evidence supports position B, which position should you believe? You should believe hypothesis A, right? No! You should put 85% confidence on hypothesis A, and 15% confidence on hypothesis B. Otherwise, you are just being dogmatic. Beliefs should be distributed in proportion to the evidence. Snapping to an extreme position is not what you want the other person to do. So don't do it yourself.

The great thing about putting degrees of confidence on every hypothesis is that it makes it much easier to respond to new evidence. For example, if some new evidence for hypothesis B arrives, you might change to 84% confidence for hypothesis A, and raise your confidence for hypothesis B to 16%. That's not a big deal. You don't have to fight against this new evidence as if it threatens some cherished beliefs. Just be happy to accept it. Say things like, "I'm a little more convinced that you might be right". It really is okay to bend a little.

Don't attach yourself to your positions. Don't say things like, "I am an atheist". It doesn't matter what you are. Truth is not some kind of democracy. We are not voting. What matters are your reasons for distributing your confidence the way you do. Those are the only things that should have any impact on others. So you might as well leave yourself out of it.

One of the strongest defenses that dogmatic people have is to feel attacked. As soon as they feel you are attacking them, it becomes easy for them to conclude that you must be bad. After all, they know they are sincerely trying to be good. Surely, only a bad person would attack someone who is trying to be good. In order to prevent that from happening, you need to keep the positions separated from the people. And that means you need to demonstrate that you don't attach your position to your identity either.

Sometimes support other positions. If you really are humble, distribute your beliefs according to the evidence, and don't define yourself by your beliefs, then you should also feel perfectly comfortable exploring minority possibilities, right? You might think that is working against your actual position. It's not. In reality, it's one of the most powerful techniques I know for encouraging the other person to do likewise.

Sometimes saying things like, "that's a really good point", or "I haven't thought of it that way before", and following up with some reasons why the other person might actually be right completely changes the tone of a conversation. Remember, you are not trying to save the other person with your brilliant arguments. You are investing in a relationship so you can help the other person start thinking again. Any changes that occur in the other person will not happen mid-conversation. They will happen months or years later, when he or she is contemplating the positive example you set long ago.

Why people become dogmatic

As a point of reference, let us consider the process scientists use to advance human knowledge:

- [Hypothesize] Scientists read each others' papers to learn what's going on in their domains of interest, and to spur them to come up with new ideas.

- [Validate] When a scientist has an idea, she (or one of her students) attempts to empirically validate the idea. (That is, they seek some way to quantify its correctness.)

- [Submit to scrutiny] Then they write about it, and submit their paper for peer review. The peer reviewer's primary job is to make sure the paper specifies exactly how to validate the results. This makes sure that everyone else who reads the paper can subject the idea to further scrutiny.

The third step in this process (peer review) has an essential role that is often misunderstood. Many people imagine that the peer reviewer's job is to scrutinize the paper and make sure that the idea is completely valid. That is actually not what peer review does. The reviewer's job is actually to make sure that the idea can be validated.

That may seem like a subtle distinction, but it is really quite important to the operation of science. In reality, peer reviewers rarely have the time or energy to repeat all of the author's experiments. So if peer review was the gate-keeper of valid science, then all sorts of bogus ideas would find ways to sneak through, and science would eventually become as riddled with superstitious nonsense as faith-based organizations. But passing peer review does not mean an idea has been scrutinized. It just means someone has confirmed that the idea can be scrutinized.

The reason science works is because peer review prevents publications from hiding behind a cloak of being unverifiable. Every time a scientist gets something past peer review, she puts her reputation on the line. If other people start to care about her claims, they might try to reproduce her results, and the truth about those claims will then come to light.

Many scientific claims are never actually tested by anyone else. That's not really a big deal because it means no one really cares. But when a scientific discovery starts to attract a lot of attention, perhaps because it is really useful, perhaps because it makes a lot of people upset, or for any other reason, its reliability will be proportionally scrutinized. Some famously exposed scientific frauds include the Piltdown Man, the Tasaday Tribe, and the Cardiff Giant.

Do these incidents of fraud indicate that there are falsehoods among scientific claims? Well, yes actually. Fraud is everywhere, and science is not immune. But these incidents also show that it's hard to maintain falsehoods on subjects people care about when you have to tell people how to test your results just to get published. There is no domain where everything that is written can be trusted implicitly. But in science, at least every claim can be reviewed. The one, two, or three reviews it received by peers is absolutely not sufficient to prove that the discovery is valid, but it should be enough to demonstrate that the work can be reviewed. So the more controversial the topic, the more scrutiny any scientific claim will have to survive. Thus ironically, the most reliable corners of science also tend to be the ones most disparaged, and therefore scrutinized.

Now, let us contrast the way science gains knowledge with the way people do it: Like science, people [Hypothesize] consider what they know from their prior experiences and observations of the world. These observations spur them to come up with ideas about the ways things are. Next, people [Validate] look for reasons to confirm that their ideas are right. And, of course, we all know people are exceptionally talented at finding reasons to claim that they are right. (This tendency is well-recognized in psychology as confirmation bias.) When people find reasons to suppose their ideas are correct, they harden those ideas into beliefs. So far, this process sounds rather similar to the one used by science, doesn't it? But what is the brain's equivalent of [Submit to scrutiny] peer review?

Suppose for example, Alice says to Bob, "I nearly died of cancer. But after six months of grueling treatments and intense prayer, I went into remission. Now I know God hears my prayers." If Bob felt that he was acting in the role of a peer reviewer, he might respond with any of the following comments:

- "The author's evaluation was more emotional than empirical. Thus, the conclusions drawn likely reflect more about the author's biases than reality."

- "In the final sentence, 'know' is an excessively strong word to use based on one anecdote. Please revise by replacing it with the phrase 'have faith'."

- "The author's evaluation of the experience neglected to consider the relevant detail of God's role in giving her cancer in the first place."

- "The connection between prayer and the final outcome was not sufficiently established. Please demonstrate why alternative explanations, such as the grueling treatments, should not be considered."

- "The single anecdote described is not sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance. Additional experiments are needed to complete this study."

But of course Bob will not say any of those things. It wouldn't even be nice! Alice wasn't expecting peer review. She was expecting friendship. And if Bob were to go around offering unsolicited peer reviews of peoples' experiences, he would very quickly run out of friends, and therefore have little influence anyway.

So because Bob is not a complete jerk, he will express something about how great it is that Alice recovered. And by recounting her story and receiving Bob's approval, Alice will become even more dogmatic in her position. And there seems to be nothing practical that Bob can do about it. So how does science deal with this problem?

Sometimes people imagine that science has some kind of authority hierarchy that passes laws about how scientists must behave. The reality is that most scientists work on their own, with very little oversight. And just like everyone else, they are perfectly free to publish ideas on their own web sites with no oversight or peer review whatsoever. So why do scientists even submit to peer review?

There is a strong culture among scientists of hating confirmation bias. For the most part, they are all sick and tired of hearing claims that cannot be validated. And they know that peer review filters out the subjective garbage so they won't have to dig through it. Most scientists won't even take a document seriously unless it has been peer reviewed. And even highly reputable scientists who would probably get plenty of attention without subjecting themselves to peer review still do it--maybe out of habit, or perhaps to show support for process that they deem more important than their own work.

So how can we fix the scenario with Alice and Bob? Should there be a rule that Alice must submit to peer review before she can share her opinions? Obviously not! Even scientists would not submit to oversight like that. Should Bob try to be a vigilante enforcer of peer review by offering unsolicited criticism of Alice's opinions? Nope. That's not how it works either. The answer is that Alice needs to be cultured in seeking critical review of her opinions.

But what can Bob do in this hypothetical scenario? Unfortunately, nothing. When that scenario started, it was already much too late for Bob to start teaching Alice about the importance of avoiding confirmation bias. That needed to start happening years earlier. Clearly, this is not a short-term kind of problem.

Addiction to confirmation bias

Signals in the brain are transmitted from neuron to neuron by electrical signals. As a person forms a new idea in her mind, new "pathways" in the brain are formed to represent it. And if her brain determines the idea has value, it releases a chemical called dopamine to reinforce the pathway.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter. It is ionically charged so that the electrical signal that passes between neurons pull it along the same pathway. When dopamine interacts with a synapse (the place where one neuron connects to another), the synapse responds by forming a more sensitive connection. That is, it causes the downstream neuron to respond with less stimulation. At a high level, the role of dopamine in the brain is to transform ideas into beliefs, and actions into habits.

Dopamine plays a central role in the proper function of the human brain, particularly for motivation and desire. Excessive amounts of dopamine in the brain has been linked with aggression, euphoria, and intense sexual feelings, while dopamine deficiency has been linked with Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia, and depression. Many of the drugs most-often abused by humans, including opiates, alcohol, nicotine, amphetamines, and cocaine, are addictive because they induce neurochemical reactions that increase the amount of active dopamine in the brain.

When a healthy brain is operating normally, it constantly attempts to forecast the sensations that will be observed next. (For example, have ever had a close friend with a habit of trying to finish your sentences? This shows that your friend's brain was doing that as he or she listened to your words. When you see someone about to get hurt, do you ever cringe with sympathy pain? When you hear a song you know, do you ever find yourself wanting to sing along? Then your brain also does what brains do.) When the brain encounters stimulus different from what it is expecting, it knows that it needs to adjust its beliefs. And when it receives the stimulus it was expecting, it responds by rewarding itself by releasing a little bit of dopamine. That dopamine then travels down the active pathway and reinforces the understanding that was just validated.

But real confirmation is not the only way to get that dopamine release. When people are in groups with people they trust, for example, the brain is much more loose with its dopamine. It is easy to observe that groups of kids often form habits together. And religious meetings seem to have evolved to create the conditions that cause the brain to bathe itself in dopamine. I hypothesize that the mental straining associated with trying to have faith in a particular idea causes the brain to overproduce neurotransmitters and associate them with the pathway that represents that idea. People who do this seem to become eager to accept any evidence they can find as confirmation of the idea they have put their faith in, and when they find something that can serve as confirmation, they quickly determine that the idea is incontrovertibly true, precisely what would happen if the associated neural pathway had been bathed in dopamine.

Of course, dopamine is not the only neurotransmitter involve in the learning process. Some other examples include: Norepinephrine makes one alert, focused, ready to respond, and activates memory. Seratonin promotes self esteem, suppresses anxiety, and promotes feelings of well-being and contentment. Oxytocin promotes trust, bonding between individuals, and feelings of affection. Acetylcholine enhances alertness, helps to sustain attention, and promotes learning. And there are many more.

I do not think it is coincidence that the emotions induced by these neurotransmitters correspond so closely with the experience that religious people call "the Holy Spirit". I think the act of deliberately striving to place faith in the ideas they are taught together in groups induces their brains to synthesize a cocktail of neurotransmitters, ready to create such an experience. And I do not think it is coincidence that deeply religious people behave in ways that mirror substance abusers. I think that repeatedly subjecting their brains to unnaturally high levels of these neurotransmitters creates a chemical dependency every bit as strong as a drug addiction. This explains why they return again and again to the behavior that gives them their fix of dopamine: confirming over and over that their beliefs are absolutely true.

I think this is precisely the vulnerability of human minds that these dangerous memes have evolved to exploit. And that gives us a critical insight into how we can effectively treat dogmatism: We treat someone with an addiction to dogmatism the same way we treat someone with a substance abuse problem.

Ridicule is ultimately counter-productive

In the 1980's, in order to combat a rising epidemic of substance abuse, schools across the United States made a concerted effort to paint drugs as being very bad. Addicts were shunned and sometimes even persecuted, and the use of drugs was institutionally painted as "not cool". And did it work? Well, yes and no. It worked very well with the people who were already least vulnerable to substance abuse. It widened the chasm between the pious abstainers and the users. But while a wider chasm may have helped to protect those who were already largely unaffected by the drug abuse epidemic, it also made recovery much more difficult for those who were separated from the "institution". Now, in order to escape from their addictions, they either had to do it completely alone or swallow a whole lot of pride and play the role of a helpless victim so they could rejoin an otherwise unwelcoming society.

If you really want to help someone who is addicted to a dangerous meme, it would help a lot to read up on treating addictions. Here's a decent place to get started. But be sure to read some of the counter-arguments available out there too. Addiction is a complex subject that will require a deep understanding on your part. But to reduce a lot of research into one statement, disparaging the problem is counter-productive.

Certain free thinkers have proposed that the answer to dogmatism is to ridicule absurd or superstitious beliefs. They have coined mantras such as, "The ridiculous deserves to be ridiculed, by definition". That may be true. But the question is not whether or not ridicule is deserved. The question is whether or not ridicule is effective. And the answer is no. If you think your job is to enforce justice upon the world, you're reading the wrong article. This article is about how to help people that you care about.

What does work with substance abuse? The answer is the exact opposite of what we thought. The answer is to clean up the addict's environment, treat them with respect, and give them love. It turns out that when addicts start getting healthy fixes of dopamine from social interactions, the pressure is reduces for them to seek it through chemical substances. Of course, that isn't the end of the matter. They still gotta wanna. But there are more effective ways to promote that than ridicule. Giving the addict love is only a start. But it's a critical start. It opens the possibility for their escape by narrowing the chasm they are going to have to jump over in order to escape from their addiction.

Similarly, when a person has been infected with a dangerous meme, the answer is not to make the person feel bad about it. It turns out that feeling bad, or thinking they are broken or sinful, is precisely what makes people feel that they need their meme. It is what keeps them trapped in a cycle of seeking regular dopamine fixes by convincing themselves again and again that their baseless beliefs must be true, not because of any empirical evidence, but because they need it so badly.

I was trapped for over thirty years in a vicious cycle of addiction to a dangerous meme. It had grown to mean everything to me. I derived my purpose in life and everything that mattered to me from that meme. I had given myself completely, absolutely, and unconditionally to sustaining that meme. I am living proof that it is possible to recover from that condition. (I'll say a bit more about my personal recovery later.) While I was addicted, one of the most effective forces helping to keep me trapped in the cycle of addiction was my belief that my meme was the exclusive source of goodness in the world. That belief, of course, was false, but I wasn't trying very hard to see that it was false. When I encountered individuals who were impatient with me or disrespectful toward my beliefs, that made it very easy for me to tell myself that I never wanted to be like them, and therefore they had nothing worth listening to. Their message may have been right, but their actions prevented me from hearing their message.

They wanted me to just start playing in their sandbox of rational thinking. But I first needed to see that being fully rational was a virtue. The most eloquent orations in the world could not have influenced me when I was not listening. But in the end, just a little listening from people who were not trying to deconvert me ended up being enough to inspire me to sort out my own problems. Don't underestimate the influential power of listening.

Seeing things from their perspective

Trust is like a tower of cards. It is constructed slowly, and destroyed very easily. And the older or more experienced the person you care about is, the more active this principle will be. So if you want to retain any influence, it is imperative to be somewhat deliberate in the placement of your words.

One of the surest ways to start behaving like a bull in a china shop is to lose track of the other person's perspective. And that can be really easy to do when the other person's beliefs appear to be so utterly dumb. Far too often, the glare of that apparent stupidity distracts well-intentioned would-be councilors. And with just a few hastily spoken words they undermine the trust they need to deliver the help they are so anxious to offer.

So let's discuss the other person's perspective. Please note that it is easy to push back or criticize apparently irrational perspectives. But that's not your job right now. What's hard is to consider and understand an unfamiliar perspective. But that's what you really need to do before you can even begin thinking about how to share your own perspective.

At time 5:19 in the video above, Dr. Dennett stated, "The secret of happiness is to find something more important than you are and dedicate your life to it." When a dangerous meme has become the source of someone's happiness, that is not something to attack. It is something to replace. That, of course, will require you to have a rational meme that provides a deeper and more meaningful foundation for happiness. You never want to pit your meme against theirs. Yours must be something they can embrace without feeling that their source of happiness is being threatened. You cannot expect them to lose interest in the dangerous meme until long after they have already embraced something better. So don't focus on crushing the dangerous meme. Focus on establishing its replacement.

When the victim of a dangerous meme feels that you are there to destroy her source of happiness, she will start building a mental tabu list. A tabu list is a list of topics that she associates with you attacking her values. Thereafter, when you bring up a topic on that list, no matter what your actual purpose may be, she will switch into a defensive mode, and eye your words like someone watching a coiled viper. If you have already caused the victim to build a tabu list, then its going to take a long time for you to rebuild a relationship of trust.

A particularly common communication error is having a completely different focus of priorities. Typically, the person who has recognized the dangerous meme (you) will be focused on the veracity of its foundation of knowledge. You are bothered that the meme is causing the person you care about to believe absurd and superstitious falsehoods. Typically, the person who has embraced the dangerous meme (the victim) will be focused on the wisdom it promotes. She sees that it teaches her to do good, to make moral decisions, and provides a sense of purpose. When you start talking about matters of fact, she will often oblige because she believes her meme is built on a solid foundation of truth. But her willingness to temporarily discuss matters of fact does not mean those facts have become her reason for embracing the meme. She is just being courteous by approaching the matter from your perspective. To her, it is a hypothetical situation. Then, thinking this is your moment of victory, you demonstrate a factual contradiction she cannot resolve. ...and that's when you discover how thoroughly you mischaracterized the situation.

No matter how great you felt about that, it was not a moment of victory. When she found herself unable to resolve her meme with reality, she was forced to retreat from the hypothetical situation. Then, her real reasons for embracing the meme come out. It gives her meaning and purpose. It is her foundation for happiness. And you offered no replacement. You were just seeking to destroy those good things. All of your arguments get added to her tabu list. And worst of all, your relationship is damaged.

The moral is, it's not really a victory if it happens on your home turf. A genuine victory will not involve tearing down, but building up. And it will not involve satisfying your priorities, but satisfying hers.

Defeating a religion with logical reasoning is rather like beating up someone's grandma. She isn't really in a position to defend herself, and it honestly doesn't make you look very awesome. But offering a more stable basis for morality, purpose, and happiness-- that's like beating her at a cookie-baking contest while wearing a sweater you knitted the night before.

No matter how much you try to justify attacking religion with reason, you will always just make yourself appear to be the "bad guy". Remember, intelligence requires both knowledge and wisdom. Even if the religion is built on a foundation of lies, it is still striving to fill a legitimate purpose. So unless you offer some way to fill that purpose better, your actions only reinforce that appearance.

Rational reasons for morality, purpose, and happiness

If you intend to take on grandma in a cookie-baking contest, a little preparation could make a big difference in the outcome. So, let's consider some rational reasons for values that are often built on foundations of superstitious nonsense:

| Superstitious reason | Rational reason |

| I find life to be meaningful because I will live forever in a place of eternal happiness. | I find life to be meaningful because it gives me an opportunity to do things of value, like help others. |

| I avoid destructive behaviors because God does not approve of them. | I avoid destructive behaviors because they are destructive and hurtful. |

| I care about others because God's second highest commandment is to love others. | I care about others because I am part of human society. |

| I am important because God cares personally about me. | I am important because I have power to affect myself and others. |

| I am optimistic because God will eventually take care of all problems. | I am optimistic because life has a long history of overcoming problems and advancing. |

| I can face death because a spirit will persist my consciousness. | I can face death because it's not all about me. |

| I know I will succeed because God is by my side. | I may not succeed, but I intend to do my best. |

| I can humbly admit that God is in charge and tells me everything I need to know. | I can humbly admit that I have much to learn, and evidence says more about truth than my intuition. |

| If I lost my religion, I would become an amoral hedonistic nihilist and do many bad things. | Your revoltion at that idea shows that you are an inherently good person who would not. |

To you, these ideas probably seem elementary, too painfully obvious to even bother discussing. But until the issues represented here are firmly resolved in the mind of the person you care about, they will undermine every rational argument you attempt to make. And after these issues are firmly resolved in the mind of the person you care about, there will probably be little need to make any rational arguments. The other person will probably figure them out on her own.

You see, knowledge only has value to the extent that it supports valid wisdom. So when a person is convinced that good moral behavior is the right conclusion, that person cannot even make herself accept knowledge that seems to say otherwise. Therefore, your job is to know how to fill out the table above with lots of details. You need to be absolutely prepared at any moment to show how rational logic sustains and promotes good moral behavior. (And if doesn't, then maybe you should consider that you don't yet have anything worth fighting for.)

Teaching people how to identify truth really does work

There are a lot of approaches to saving someone from a dangerous meme that do not work. Attacking the meme does not work. Ignoring it doesn't work. Mocking its victims definitely doesn't work. And even respectfully debating the logical basis of the meme does not seem to work very well. (Eventually, everyone figures out that's just the same as the first approach with a candy coating.)

A lot of people have thrown up their hands in frustration and exclaimed, "Nothing works! There is absolutely no way to influence a dogmatic person. You just have to hope they fail to indoctrinate their kids, and wait until they die." But that is not an acceptable answer. These are people we care about. And you don't just give up on people you care about.

Fortunately, there is something that works. It's not something trivial to pull off. And it doesn't work every time. But it does work well. The approach that works is teaching people to use the scientific method.

I can offer four small bits of evidence to support my claim that teaching people to use the scientific method actually works to fight dogmatism. I have a reason, a statistic, and two anecdotes. But before I present my evidence, I want to be clear about what I am actually claiming:

I am not claiming that telling someone to use the scientific method will have any beneficial effect. Teaching requires a whole lot more than just telling people what to do. Teaching requires you (the teacher) to understand the subject matter. You cannot teach something well unless you understand it well. Teaching requires you to listen to your students. You cannot build a bridge between two points if you only know where one of those points is. And teaching requires a whole lot of patience.

And I am not saying that you should go tell someone that science has debunked their stupid meme. That would undermine everything you are trying to teach, and would make you look conceited and shallow at the same time. The method that I claim is effective at combating dogmatism is teaching people to use the scientific method. And that's it.

I know, you really really want to tell the other person that their meme is a scam. You want to prevail. You want to be right. You want to be recognized. But if you care about the other person, you will let those things go. Your goal should be no more than to teach the other person how to identify truth. Then after that, it shouldn't really matter to you what conclusions they arrive at. After all, if they are using a valid method to determine what is true, who is to say that you aren't the one who has been deceived?

And one more time: Your goal should be to teach the other person how to help themselves. And that's it. Do no more. First teach a valid method, and then trust the other person to do the right thing.

Okay, so now that you know exactly what I am claiming, here is my evidence:

(1) A little reasoning: The mind needs to believe something. It is not easy to just throw out a belief, until there is something better to replace it with. And the whole reason people become dogmatic in the first place is because they use methods that promote cognitive biases. There is something recognizably honest about the scientific method. If I were to describe the scientific method in one line, I would say the scientific method is to try to tell it how it is, and not how you want it to be. It's not really a concept that is foreign to anyone, but it is a concept that takes practice to really become familiar with. Of course, everyone thinks they are honest, but people have some pretty funky ways of defining honest. The scientific method is just trying to do it right--no fancy complications, just humble openness and patient dedication. And when that takes root in someone's mind, it starts to offset biased methods. One cannot be unbiased and biased at the same time. So, slowly, the scientific method starts to ground a person's knowledge to truth. And the rest just happens on its own.

(2) A statistic: This article provides statistical evidence that scientists are significantly less likely to believe in God than the general public. The first chart in the paper makes it pretty clear that there is a big difference between the two groups regarding beliefs. Of course, this does not prove that familiarity with the scientific method is what caused those scientists to leave faith in God. Maybe people who already lack faith in God are more likely to become scientists, right? Well, the last chart in the paper says something rather important too. It shows that the more time one spends being a scientist, the less likely they are to continue to believe in God. Interestingly, among the general public, the older generations are significantly more likely to believe in God, so there is definitely something in the domain of science working to evaporate dogmatism. I claim that thing is the scientific method itself.

(3) An anecdote: Of course anecdotes are not very scientific. But I am not trying to be scientific right now. I am trying to persuade you to teach the scientific method. Anecdotes are great for being persuasive. Anyway, my anecdote is this: I was a very hardened dogmatic person, and learning to use the scientific method cracked my shell. I'll save my full deconversion story for another time, but I'll provide a few salient details here. I was a very devout believer in my religion. I was very active. My testimony meant more to me than my life. I cared for little else besides pleasing God. Of course, I had heard arguments against the existence of God, but my heart told me they must be wrong. My religion taught me to do things I knew to be good, and how could that possibly be wrong? My religion also taught me to place great value on truth. That's what ended up drawing me to science--I felt that it would help me draw closer to God. I studied science at a religious school that worked very hard to reinforce faith and integrate it with secular learning. But as I started to become familiar with the scientific method, I also started to realize that it was the only valid method for identifying truth that I had ever been taught. I believed that God himself wanted me to be honest. So no one needed to present any compelling new arguments against God. My own desire to be honest compelled me to investigate the matter and find the truth. Once that was set into motion the outcome was inevitable. Leaving my faith was a long and grueling process, but that's another story. The lynch pin of my story is that I could not both understand how to identify truth and be kept from it at the same time. As soon as I really learned how to identify truth, the rest was destined to eventually happen on its own.

(4) Another anecdote: I went on to teach science at a University. On one occasion, a certain student commented to me in passing that he had moved away from his oppressive fundamentalist religion. Since religion is not a common topic of discussion at a secular university, I invited him to chat in a more private setting. When I asked him why, he credited a particular lesson I had taught, and proceeded to show me how it led him to draw his own conclusions on the completely different subject of religion. That student knew nothing about my own position on religion, and the only time I had ever taught him was before I myself had deconverted from a fundamentalist religion. As a believer myself, I had certainly not made any effort to disparage religious beliefs. Naturally I began to wonder, if one student had been willing to come out about losing faith because of me, how many other students had I already influenced in a similar manner who remained in the closet? Many people have a perception about university professors, that they are predominantly liberal activists with chips on their shoulders against religion. There may be some like that, but I was a conservative professor who was himself still religious. I determined that my job was to teach students how to think, not what to think. As years passed, a great many students started approaching me to thank me for making an impact in their lives. Only a few of them ever mentioned religion, but the vast majority of them mentioned my approach to teaching. My impression is that you have much more influence on people when you teach them to think for themselves. ...but that's just an impression. Please don't accept it as established truth until you can see for yourself that it has really been established as truth.

I wish I had more evidence, but that's what I've got, and I think it's enough to offer some general guidance. I think it is clear that people have a need to draw their own conclusions. As the old adage goes, a man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still. It is not your place to tell anyone what they need to believe. But you can teach people how to recognize manifestations of reality, and separate it from manifestations of confirmation bias. Then, trust them. If your beliefs have any real value, they can defend themselves. So teach the other person how to think. Then back off and let them do it. I think that's the grand secret to treating infections of dangerous memes.